“Yes likes challenges.” So says Yes guitarist Steve Howe, and the proof is in the output. The band has been out on the boards in the U.S. and Canada playing a set comprised of three full albums: The Yes Album, Close to the Edge, and Going for the One. On their upcoming summer tour in July and August, they’ll be doing two full albums: the first-ever full run-through of Fragile and Close to the Edge, in addition to an encore centered on the band’s greatest hits. Plus, an album with new lead singer Jon Davison, Heaven and Earth, is slated for a July release. And, of course, there are the sonically brilliant 5.1 mixes of Close to the Edge and The Yes Album on Blu-ray as masterminded by Steven Wilson — and more are on the way, with the band’s blessing. Howe, 67, and I ... Read More »]]>

Going for the Five: Yes 2014, from left: Steve Howe, Jon Davison, Alan White, Geoff Downes, Chris Squire. Photo by Rob Shanahan.

“Yes likes challenges.” So says Yes guitarist Steve Howe, and the proof is in the output. The band has been out on the boards in the U.S. and Canada playing a set comprised of three full albums: The Yes Album, Close to the Edge, and Going for the One. On their upcoming summer tour in July and August, they’ll be doing two full albums: the first-ever full run-through of Fragile and Close to the Edge, in addition to an encore centered on the band’s greatest hits. Plus, an album with new lead singer Jon Davison, Heaven and Earth, is slated for a July release. And, of course, there are the sonically brilliant 5.1 mixes of Close to the Edge and The Yes Album on Blu-ray as masterminded by Steven Wilson — and more are on the way, with the band’s blessing. Howe, 67, and I talked about those 5.1 mixes, what we’ll hear on the new album, and what constitutes a musical legacy.

Mike Mettler: I’m so pleased to hear that you’re doing all of Fragile on the upcoming summer tour.

Steve Howe: Fragile is pretty accessible, and some of it we haven’t played for a helluva long time. It’s going to be a nice mix.

Mettler: Is there anything on it you’re just itching to play again?

Howe: Well, we all like “South Side of the Sky.” Things like “Five Percent For Nothing” are novelties because they’re so short. [“Five Percent” is 35 seconds long.] But we’ll dance through the entire album. It’s a challenge, and Yes likes challenges. Doing three albums was a big undertaking in itself, and we’ll get Fragile sorted. It’s really how close we get to the arrangements. We try to get as close as we can, but that makes different demands on different people, so I hope everybody is able to live up to it.

Mettler: I happen to think the surround-sound mix Steven Wilson did for Close to the Edge is one of the best ones I’ve ever heard. What did you think of it?

Howe: Yeah, it’s amazing. I was involved with some of the mixing, because he wanted some of my input. And since we were both in the U.K. at the same time, I got together with him to listen to some of it and talk about some of the details.

Mettler: What did you like the most about hearing this album in 5.1?

Howe: It’s not an easy question to answer. [laughs] He’s trying to get as close as he can to the original mix with what he was doing with the 5.1. At different times in my life, I’ve liked quadraphonic and 5.1, and so it’s really about having the hi-fi experience. And other times, it’s about having enough time for listening to things that way! But I admire him for doing it, and the label [Panegyric] for pushing to do it and giving us so many options in one release.

Mettler: Right — you have the needle drop, the updated mix, the original stereo, single edits, and the surround. The music on Edge is so enveloping to begin with that Steven’s 5.1 mix really puts us in the middle of what you guys were playing. Any moments you’d consider the most interesting?

Howe: You can hear the separation with the very fast organ playing at the beginning of “Close to the Edge.” It was overdubbed because Chris [Squire, bassist], Bill [Bruford, drummer], and I played together at the front end as a trio, and then we added Rick [Wakeman, keyboardist], who was playing remarkably fast — practically a double-speed version of the riff Chris and I played. But that kind of allows for the separation you can hear there.

Mettler: How involved were you with what Steven did for The Yes Album?

Howe: In a similar capacity. He wanted me to listen to what he did and then give my input. So I sat down with him and listened to it all. And before the Canadian tour started, I sat down with Steve for an afternoon and listened to [the next one Wilson is doing, which hasn’t been officially announced yet; sorry!—The SoundBard]. I did hear a few things, and they were able to take my comments and incorporate them as well as they could accommodate them. They’re very meticulous, in the way they want to match the original, or get as close to the original as humanly possible. Which in itself is a sort of paradox, because you have the original. [laughs] It’s also an unusual mix, but I’m very proud of Steve and that he’s going the whole distance. I’m just helping him where I can.

Mettler: He was very appreciative of you when he and I spoke about Edge in 5.1. He said having your input was invaluable to help keep things as faithful to the original as possible, and not, to use his words, “modernize it.” You were able to ground what he was doing.

Howe: That’s nice. On [the next one], there’s definitely a sonic improvement. There is a difference. It’s something that’s very, very hard to define — an openness to the higher registers of the music. It wasn’t easy doing all that with the technology of the time. Lining up every machine in the chain had to be perfect, and so did the phasing, the bias, the quality of the tape — it was all relying on so many things that are now blown away because everything is digital, you know. [laughs] It’s less reliant on lining up the accuracies of the tape, lining up engineers, lining up machines, the feed quality, and all the other things I mentioned. It was so boring then, and you just had to put up with it, but it was endless. The speed of the machines had to be so accurate to really be taken seriously, but nothing could ever be 100 percent perfect.

Mettler: There was a DVD-Audio 5.1 mix of Fragile in 2002. Do you think that’s an album Steven will get to revisit?

Howe: Maybe, yeah. That was one I mentioned to Steve. Although I appreciated what Tim [Weidner] did, I was unhappy that he included things that weren’t on the original record. Steven is only committed to having master parts on the recording — otherwise, it trivializes the idea. I was actually quite upset at what was on “Roundabout” — I mean, it’s fun that it’s different, but if it’s different, it’s wrong. I’m not too precious about it because not a lot of people heard it, but Steven’s remix will be thorough and consistent, and he will get around to Fragile. There are some issues with finding all of the masters, but we’ll get there.

Mettler: Is it open-ended that as many of the catalog masters you have in hand will get done in surround?

Howe: I don’t think we should say yea or nay yet, because there could be logistical things or even a question of taste. I mean, providing we don’t make a record sound worse [MM laughs], and we can make some of them sound even better. We’ve all got our favorite ones that we don’t like. I’m not going to say what it is, as there is an album like that which was disappointing sonically, and even the writing was a bit disappointing, and it’s in the ’70s —

Mettler: It wasn’t one that came out in 1978, was it?

Howe: [laughs] I’m not going to even go there! But there is one that’s like that sonically, structurally, and musically — everything about it. It’s not that it’s dreadful; it’s just that we didn’t quite get it right. I don’t know if a remix would make it right, but I really can’t say because I don’t think it could, because if you’re going to be true to the original, then you have to base it on the original.

Mettler: Well, what you could do is give people the original mix, just like you’ve done with Close to the Edge and The Yes Album — here’s the needle drop and the original stereo version, and now here’s the “updated” mix. Will we get to hear the new album, Heaven and Earth, in surround?

Howe: That’s a good idea. I mean, it’s funny that we’re doing music that’s 40 years old in 5.1, and yet we’ve just recorded Heaven and Earth and Fly From Here a few years ago [2011], and it might be more relevant to do 5.1 with those two releases. We’re a little backed up on time because of the touring, but maybe that could be a discussion later in the year so that we might have a 5.1 out by then. That’s a pretty cool idea.

Mettler: How would you characterize the sound of Heaven and Earth? You worked with Roy Thomas Baker as the producer.

Howe: I would say it sounds pretty different for us. It follows more the kind of material we’re playing with [current lead singer] Jon Davison and what he’s been writing, because Benoit David [vocalist on Fly From Here] didn’t really write with us. But this time, we are presenting a new writer alongside what Chris and Geoff [Downes, keyboardist] and I are writing. It’s the kind of an album that has a lot of freshness, and I think that’s quite a healthy thing. The cross-writing is quite interesting, as Jon has written with most of us. There’s quite a collaborative sense that Jon brought into play a lot. And his voice — we’ve gotten to see the effect of that element because of Roy Thomas Baker as we checked the mixes and got the whole feel. I’ve become quite happy with the album, and think it will be somewhat more of a surprise than Fly From Here.

Mettler: Do you remember the very first record you bought with your own money as a kid?

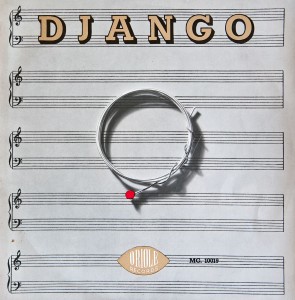

Howe: Yep! I do! There were two, if I’m allowed to mention two — there was Elvis Presley’s album, Rock ’n Roll [1956], with “Blue Suede Shoes” on it. I bought it from a friend who said, “I don’t really like this; do you want to buy it cheap?” And I said, “I’ll buy that!” And there was another friend of mine who had a 10-inch record with the picture of a guitar string on it, a Django Reinhardt record [Django, 1954], and I bought that too. Got them more or less at the same time, and they’re both records that have stayed with me my entire life. And I virtually couldn’t do without either of them. They’re the most remarkable records, because they went so deep to my personality as a guitarist and a musician.

Mettler: You can hear it as part of your DNA.

Howe: It is. Those records are very, very important. But then I bought Teensville by Chet Atkins [1960], and that brought some more into it. And as I’ve said before, Chet Atkins is the most central, singular great guitarists I’ve heard. I’m big on his early stuff, especially the fingerpicking.

Mettler: Earlier, you mentioned how important separation is in a surround mix. Your final thoughts on that idea?

Howe: Surround’s a funny animal. It’s really about separation. The separation is what makes for a good surround mix. There’s some great separation in these mixes, and I suppose that’s the main point of having these 5.1 mixes. Sometimes there’s an emphasis on reverb and an emphasis on “theater”— but 5.1 is also for theater, so in a way, we’re redesigning music around what’s made for a theater. So I say, great! Every time Bach is recorded from a cylinder to a 78 to a 33 to a 45 to a CD to a MiniDisc to an 8-track to a cassette [both laugh] — I mean, Bach’s music has gone through the same kind of transition that our music is going through. It’s keeping up with the times. It’s being reinterpreted by other people, redesigned through great recordings that can be rereleased over time.

And certainly J.S. Bach has one of the greatest, most fascinating histories of being reinterpreted by people like Glenn Gould and many, many others. Bach was one of the most amazing geniuses music has ever had because he had to do all that himself. He was thinking that music written for an organ wouldn’t necessarily stay on an organ — maybe there could be an arrangement for a choir! And that’s what he did himself. He was totally unprecious about the format. The format of the music isn’t important — what’s important is the music. And if it can transcend the performance, then I think you’ve got music that evidently will last.

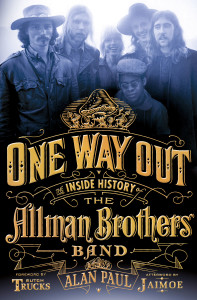

]]>If knowledge is power, then Alan Paul is the chairman of The Allman Brothers board. His definitive inside history of The Allman Brothers Band, One Way Out (St. Martin’s Press), is one of the most thorough, in-depth, and best-researched rock biographies I’ve had the pleasure to read — and if you know me, you know I pretty much read ‘em all. Though I’m a diehard Allmans fan and I’ve personally interviewed ABB members Gregg Allman, Butch Trucks, Warren Haynes, and Derek Trucks, I learned something new with just about every turn of the page. Alan’s first-hand reporting and meticulous research, presented in the oral-history format and strategically interspersed with his own insightful commentary, is so spot-on that one could almost retitle the book One Way In.

I first met Alan in early 1991 when I started writing freelance for Guitar World (he remains a ... Read More »]]>

If knowledge is power, then Alan Paul is the chairman of The Allman Brothers board. His definitive inside history of The Allman Brothers Band, One Way Out (St. Martin’s Press), is one of the most thorough, in-depth, and best-researched rock biographies I’ve had the pleasure to read — and if you know me, you know I pretty much read ‘em all. Though I’m a diehard Allmans fan and I’ve personally interviewed ABB members Gregg Allman, Butch Trucks, Warren Haynes, and Derek Trucks, I learned something new with just about every turn of the page. Alan’s first-hand reporting and meticulous research, presented in the oral-history format and strategically interspersed with his own insightful commentary, is so spot-on that one could almost retitle the book One Way In.

I first met Alan in early 1991 when I started writing freelance for Guitar World (he remains a senior editor there today), and whenever he’d sink his teeth into stories about the likes of Albert King, The Doors, Lynyrd Skynyrd, and ZZ Top, I knew I’d be in for a damn good read. Recently, after devouring One Way Out, I asked Alan about the highlights of The Allman Brothers Band’s recorded legacy, Duane Allman’s involvement with Layla, and what he thinks about the ABB’s infamous runs at the Beacon Theatre in New York — and whether the band will go on.

Mike Mettler: What was the most shocking and/or surprising thing you learned while researching One Way Out?

Alan Paul: Not any one thing as much as an accumulation of details helping me — and hopefully my readers — understand the dynamics of the relationships between all members of the band. Duane Allman was the one with the vision for this very different band, and he was the one everyone looked up to and he held the thing together. I knew all that, but not the full extent of his charismatic leadership and the struggles to hold it together for so many decades without him.

I also developed an even deeper understanding of the tensions that led to Dickey Betts’ ouster from the band and the extent to which being in the band with him was living in a constant state of being bullied. It all blew up in 1996 in an Idaho hotel room. I outlined the details, which involve a knife, in the book. I knew the basics, but not the specifics, until my reporting for One Way Out. It’s all complicated, because Dickey pulled the thing out of the fire after Duane’s death and was the undisputed musical leader afterwards, and they never would have had the success they did without him, but it just reached a breaking point.

I also had not really realized that [bassist] Allen Woody was basically fired from the band — and it was all because he stood up to Dickey in that hotel room.

Mettler: If you had the chance to go back in time and meet Duane Allman, what would you have asked him?

Paul: Well, I’d most like to sit in the front row and listen to him play! What I’d really be curious to know is to what extent he envisioned what the band would sound like and how he was so sure in meeting and hearing each member that they were right person for the group. His vision of this thing and his ability to find the right people amazes me.

Mettler: Same Q about Berry Oakley.

Paul: Berry and Duane had an amazing relationship. As harmonica player Thom Doucette told me, Duane would think of something he wanted done, and Berry would make it happen. [Longtime Allmans roadie] Red Dog called him The Deacon. I don’t know what my question for Berry would be. I would just like to hang out with him because he seems like an amazing guy. [Original ABB bassist Oakley died after a motorcycle accident in Macon, Georgia on November 11, 1972, three blocks from Duane's fatal motorcycle accident on October 29, 1971.]

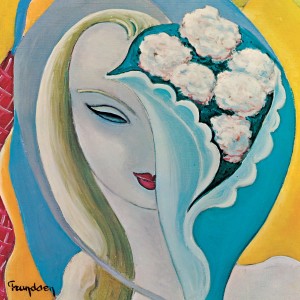

Mettler: On page 84, Eric Clapton says that he and Duane were “instant soul mates.” Would you agree? How important were The Layla Sessions to Duane as a player, and, ultimately, to The Allman Brothers Band?

Paul: I’ll have to take Eric’s word for it! By all accounts, Duane felt the same, so yes, I definitely agree. I’m not sure how important the sessions were to The Allman Brothers Band because they were on such a roll and really peaking already.

I would say that the sessions gave Duane confidence, but he never seemed to lack that. I think the sessions were certainly crucial to his overall reputation and allowed a lot more people to hear him — though a vast majority still have no idea it’s him. Most people think it’s all Eric. The fact remains that Duane wrote and played Clapton’s most famous lick, and I truly believe that Duane was who Clapton wanted to be. There’s no comparison in their playing in my mind; Duane is light years ahead.

Mettler: What’s your favorite song featuring Duane on the Layla album?

Paul: I love all of the interplay on Layla, but if I had to pick, I’d go for “Why Does Love Got to Be So Sad” or “Have You Ever Loved a Woman.”

Mettler: Do you think Dickey’s “Ramblin’ Man” changed the group’s direction and/or its leadership?

Paul: I think it reflected a change in leadership and direction more than it changed it [the band]. However, the success of the single and all that followed — stadium tours, etc. — no doubt solidified Dickey’s role as leader, not least in his own mind.

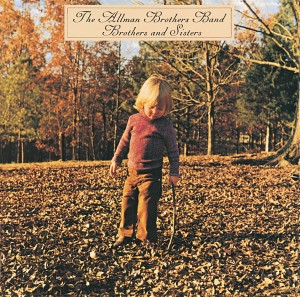

Mettler: Why is Brothers and Sisters an important album in the Allman Brothers canon?

Paul: Brothers and Sisters is a crucial album in the canon, because it definitively showed there could be life after Duane. Last year’s expanded box set is a delight, not least for a fantastic live show it includes [Live at Winterland, September 26, 1973, on Discs 3 and 4]. The way in which pianist Chuck Leavell and bassist Lamar Williams quickly and seamlessly integrated, subtly changing the band’s direction while retaining their essential nature, in the wake of the losses of Duane and Berry, is quite remarkable.

Mettler: Given the “lean years” of the mid-’70s to the late-‘80s, do you see a throughline from 1973’s Brothers and Sisters to their recording resurgence, 1990’s Seven Turns? The title track to Seven Turns is one of my personal favorite ABB songs, by the way.

Paul: Sure. Dickey Betts’ emerging leadership as a singer and songwriter for one thing, and the ability to integrate new talent and keep growing — on Brothers and Sisters with Lamar and Chuck and on Seven Turns with Warren and Woody. And I agree that “Seven Turns” is a great song.

Mettler: You’re a guitar player — what’s your personal favorite Allman Brothers songs to play?

Paul: I love playing “Blue Sky,” “One Way Out,” and “You Don’t Love Me.” I’m more of a rhythm player and singer and haven’t really tackled the more complex songs like “Jessica” and “Liz Reed.”

Mettler: What’s your favorite Allman Brothers song to just sit back and listen to?

Paul: I love listening to a lot of it, but “Dreams” and “Blue Sky” are probably my favorite kick-back songs. The former encapsulates the Gregg songs, the way they band incorporated modal jazz themes from Miles and Coltrane and Duane’s incredible depth. The latter is my favorite Dickey Betts’ major-key song and one of the finest examples of Dickey and Duane’s complementary playing.

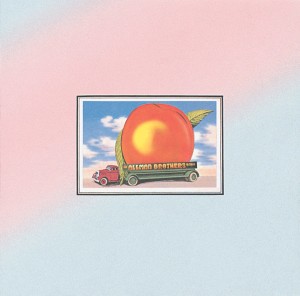

Mettler: In the Acknowledgements section of One Way Out, you mention that your brother David turned you on to Eat a Peach. What year was that, and how old were you?

Paul: That was in 1978, when I was 12 years old. I was already a music freak who carried a little transistor radio with one of those white ear pieces around listening to music all the time. I had heard The Allman Brothers on the radio plenty and certainly knew “Ramblin’ Man” and “Jessica,” which were pretty big radio hits. My first actual memory of The Allman Brothers was going with my brother to see a talent show where this dude in a fake silk shirt with a little moustache got up and sang a karaoke style version of “Ramblin’ Man.” I have no clue how he got that backing track, but I thought it was the coolest thing I had ever seen.

Mettler: What was it about Eat a Peach that hooked you on the band?

Paul: It’s hard for me to retrace my steps to being 12 and know what the attraction was, but the talk of brotherhood meant a lot to me, and the artwork on the inside gatefold fascinated me and pulled me into an alternate universe that helped the music come alive. That’s why I was so thrilled to have the same artist, W. David Powell, provide the killer artwork for One Way Out’s end pages.

Mettler: What was the first record you bought as a kid with your own money? What kind of impact did it have on you?

Paul: Man, I have no idea what was first, but I bought a lot of records at National Record Mart in Pittsburgh. I bought tons of 45s before I ever bought an LP. Some early ones I remember buying were Terry Jacks’ “Seasons in the Sun,” some Partridge Family, and Steve Miller Band’s “The Joker.” One year, my big Chanukah present was a Glen Campbell album I had begged for. I bought everything: Cheech and Chong, Allman Brothers, Lynyrd Skynyrd… all of it had a huge impact on me.

Mettler: In the Appendix, you cite Idlewild South at the top of “The Peaches” list of their best albums. Tell me a bit more why you think it’s the ABB’s greatest recorded work.

Paul: I think that “Don’t Keep Me Wondering” and “Please Call Home,” both on Idlewild, are tremendously underrated Gregg songs. It also includes “Midnight Rider,” “Revival” — which is not my favorite song, but includes heavenly guitar harmonies — and the original version of “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed.”

The other contenders would be Brothers and Sisters and Eat A Peach. The reason I chose Idlewild is B&S does not have Duane, and Eat A Peach is only a partial studio album, filled out with great live tracks. If you put a single album together of Eat a Peach studio cuts, it would include “Blue Sky,” “Melissa,” “Stand Back,” “Les Brers in A Minor,” “Little Martha,” and “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More,” and it would be a tremendous studio album.

Mettler: When was the first time you wrote about the ABB, and who was the first band member you interviewed? How did that experience go?

Paul: In 1990, I was living in Florida on the verge of giving up on being a writer and going to grad school to become a teacher. I got an assignment to write about them in Pulse. I was excited and went out and bought Dreams, their box set, and spent hours listening to it and Seven Turns. I became completely re-engrossed; the experience of writing that article was so profound to me — not just because I interviewed these guys for the first time and wrote about them, but I spent so much time listening to the music and re-immersing myself in it. I interviewed Gregg, Dickey, Warren, Woody, Phil Walden, and Tom Dowd — I went all out!

Then they came to Tampa. I hadn’t finished the article yet, and the show blew me away. It was incredible that they had reinvigorated themselves with Warren Haynes and Allen Woody. Warren made the biggest impression on me because he was standing up there with Dickey and holding his own, and they had new material, which gave them fresh life. I was still seeing The Grateful Dead, and I just started getting more and more disenchanted with their shows. I thought that these two bands were doing similar things, but The Allman Brothers were doing it a million times better.

Then I finished the article, and I went on a trip to Wyoming with my friend Art. We only had a couple of cassettes with us, and one was a 90-minute compilation I’d made from Dreams. As we drove back toward Chicago, we heard on the radio, “Tonight! The Allman Brothers at Tinley Park!” and we just looked at each other and smiled, and drove to the amphitheater. I somehow got tickets and passes from Epic Records, and it was epic! That’s why those two shows made the list.

Mettler: What did you think about Gregg Allman’s autobiography, My Cross to Bear?

Paul: I know too much about how the sausage was made to asses the meal fully, but it’s a good read that presents Gregg’s version of events.

Mettler: When and where was the first Allman Brothers show you saw? How did it affect you?

Paul: Civic Arena, Pittsburgh, 1980. I was thrilled to be there and did not realize it was a horrible era.

Mettler: How many times have you seen them to date? Do you have a particular favorite Allmans show out of all the ones you’ve seen?

Paul: I have no idea how many shows I’ve seen. I’m not a counter. I’d like to have a nice round number to throw out there, but it’s more than 100. There have been a few favorites: the first two times I saw them with Warren Haynes blew my mind. That was 1990 — first in Tampa, then Chicago. I’ve seen so many great ones at the Beacon. In the early ’90s, Dickey and Warren were just killing it. Seeing bluesman Little Milton with them was a thrill, and their 40th anniversary run was tremendous.

Mettler: You got to see all the shows during The Allman Brothers Band’s most recent run at The Beacon Theatre in New York City, the last time they’ll do that there with both Warren Haynes and Derek Trucks as full-time member of the band. How do those shows compare with the many other Beacon shows you’ve seen? What is it about the Beacon that makes it so special to see the ABB play there?

Paul: They played 10, and I went to all of them. I don’t think it will be the last time they are there, because they had to postpone the last four and have promised to reschedule. I think they were leaning toward another fall run anyhow. We’ll see.

Every Beacon show is different, which is part of what makes them so special. There’s just something that goes on in that room, involving the band and the crowd, and the size and the way the room feels and sounds that is different. I’ve seen so many shows there that it’s hard to assess what makes them different. I thought the first few were very solid but a bit reserved, and that they got looser and looser and were really hitting a groove when the run was cancelled.

Mettler: Who do you think they’ll tap to join the band after Warren and Derek actually leave? Who would you like to see them ask to join?

Paul: I really don’t know, and it’s not clear that they will continue. I would prefer them to stop touring or go a completely different direction — like adding a pianist and a sax player or something. I don’t want to see them diminished or hiring guys to play established licks, which is contrary to the whole tradition.

Mettler: One hundred years from now, how will people view The Allman Brothers Band?

Paul: They will still sound both ancient and modern, as they have since their first album, and they will be regarded as one of the greatest rock and roll bands ever. The music does not ever sound dated or unnatural.

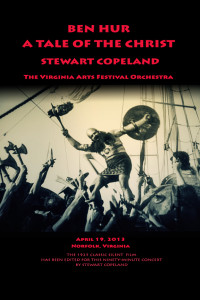

]]>Never let it be said that Stewart Copeland has idle hands. The innovative Police percussionist and ace composer has been working tirelessly on composing a soundtrack to MGM’s 1925 silent film Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, which, in addition to being a legendary broad-sweeping and groundbreaking epic tale, is on record as being the most expensive film made in the silent era. Copeland’s score receives its world premiere Easter weekend on April 19 at the Virginia Arts Festival in Norfolk, Virginia, where it will accompany his 90-minute edit of the movie.

Recently, Copeland, 61, and I discussed how restoring Ben-Hur was both invigorating and taxing, his philosophy about surround-sound scoring, some of the secrets behind his infamous snare drum sound, and a few Police-related matters.

Mike Mettler: I’m extremely fascinated about your Ben-Hur restoration.

Stewart Copeland: Well, it is a humdinger. It all began with an ... Read More »]]>

Never let it be said that Stewart Copeland has idle hands. The innovative Police percussionist and ace composer has been working tirelessly on composing a soundtrack to MGM’s 1925 silent film Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, which, in addition to being a legendary broad-sweeping and groundbreaking epic tale, is on record as being the most expensive film made in the silent era. Copeland’s score receives its world premiere Easter weekend on April 19 at the Virginia Arts Festival in Norfolk, Virginia, where it will accompany his 90-minute edit of the movie.

Recently, Copeland, 61, and I discussed how restoring Ben-Hur was both invigorating and taxing, his philosophy about surround-sound scoring, some of the secrets behind his infamous snare drum sound, and a few Police-related matters.

Mike Mettler: I’m extremely fascinated about your Ben-Hur restoration.

Stewart Copeland: Well, it is a humdinger. It all began with an arena tour [in 2009] where they staged Ben-Hur live in the arenas with a full-on chariot race and pirate battle; the whole schmear.

Mettler: Why did you decide to tackle this as a project?

Copeland: It was an incoming call way back when the arena show went up. I wasn’t a particular fan of Ben-Hur — yet. But as I got into it with the book, the show, and the two movies — the Charlton Heston one [1959], and the 1925 one, the one I worked on — I got deep into it.

Mettler: I was looking at some of the 1925 footage you posted online, and it’s astounding what was done back then. I kept thinking, “This was shot in 1925?”

Copeland: They had to do it all in front of the camera! It was the biggest movies of the silent era. It cost 4 million [said with Dr. Evil inflection] dollars. Getting the print out of deep freeze was an adventure too. It took a week to defrost this 80-year-old piece of celluloid, and the last time it was seen was in the ’60s, when they burned a video from which the DVD that’s out there was derived. That’s what I originally cut up to make my version of the movie, because the music I wrote had to match with the movie I recut. After years of pursuing this at Warner Bros. and navigating the labyrinthian divisions of this giant corporation that owns this material, it just took a while to get from one division to the other and work its way through the system to get to the point where I could actually get my hands on the original piece of celluloid. It looks like a hybrid they put together from two or three prints that were out there in the theaters. They got the cleanest footage from each one, and stuck it all together. The movie was made in 1925, they re-released it in the ’30s, and it’s got a checkered history.

The version I’ve got, I had to curate. It’s not actually black and white, it’s kind of gray and white at this point. [both laugh] So I had to get deep into the balance of the blacks and the whites and process every single shot of the movie, as well as cut down a 2½-hour movie down to 90 minutes, which was an adventure. Having done that, every single shot in the movie had to be treated. Different cameras were used, running somewhere between 18 and 22 frames per second, depending on which camera they were using, and who was cranking that day.

It’s really something, but technology aside, what they did in front of the camera was colossal. The burning Roman galleons crashing into each other, the thousands of extras blazing away and falling into the sea — a few people died in that because the ships did actually catch fire. The production value, the scale, and the spectacle is all really something else. You’re dealing with the frame shape and things like that, which are really small compared to the punch of the movie itself.

Mettler: You’re literally turning into your own Criterion Collection division with this project.

Copeland: No one has ever done it quite like this because I’m presenting the film as a concert, which has directed the way I’ve had to do the edit. And there will be those haters out there, those purists who will come after me with pitchforks, and I’ll try to mollify them as such by saying the original is still there in the box set with the Charlton Heston movie. And that’s definitely worth checking out, but the film looks much better now. Going straight back to the original from digital, there’s just a higher resolution. It looks much better than it did when they transferred it to video, which is a terrible medium.

Mettler: Will you record any of the performances for release on DVD or Blu-ray?

Copeland: At some point. I would not be surprised if we did that.

Mettler: Considering you compositional skills, I’d love to hear a full surround-sound mix.

Copeland: Well, the thing is, at some point, it crosses the line where I’m taking [director] Fred Niblo’s masterpiece and carving it up in a way that he may or may not have approved of. And I think I’m on the right side of the line when I’m doing a concert with a big orchestra, and the drums. The film is a part of that, and I’m not making any representation that this is his movie.

But if, for instance, someone were to record the concert to put out a DVD, that would require a whole other examination of the conscience. I have enormous respect for Fred Niblo. I’m very, very respectful while I’m screwing around with what he did. I’m trying to follow his logic.

Mettler: Does surround sound interest you as a film composer?

Copeland: Not so much, actually. I found that when I was working in film, whenever music came out of more than two speakers, it kind of lost its punch. There’s something to do with phasing, and there’s a lot of voodoo connected with how do you get it to sound good in 5.1 or 7.1. I’ve never succeeded. Every time we threw it [a score] to surround sound, it lost its punch. It’s coming out of stereo, or LCR — left, center, right — in front of you, then it kicks.

That’s just an audio thing. It’s counterintuitive. You would think the music would sound great, having it coming from all around you. And indeed it does, if you’re sitting in the middle of the orchestra. But the way speakers work — I just never quite succeeded in keeping the punch while having the surround.

Mettler: I agree that feeling like you’re in the middle of an orchestra, or any performance, is the best use of surround.

Copeland: Yeah, the thing is, it can be done. A buddy of mine in Primus, Les Claypool, really got into it. He played me some surround he did where it really does rock. And that’s Primus: a heavy, hairy rock band.

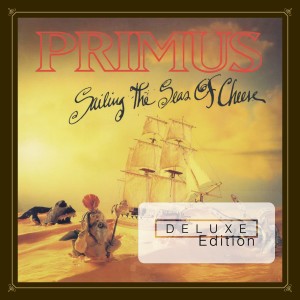

Mettler: I just talked to Les a few weeks ago, in fact. I think the surround mix he did last year for the Deluxe Edition of [1991's] Sailing the Seas of Cheese is fantastically immersive.

Copeland: Ok, yes, that one works. He had already made the record, and he’s gone back in and devoted himself entirely to achieve a good result in surround. That’s a mission all unto itself. And as he showed there, it can be done.

Mettler: Looking at it that way, would you be able to do that with some of your own work from the past, like, say, The Rhythmatist [1985]?

Copeland: Years ago, too many years ago, we did surround for a live Police album.

Mettler: Right, the Syncronicity Concert.

Copeland: From back in the day [1984]. At that time, it seemed like it was ok. You be the judge. We did it here in Los Angeles, and I don’t think we had any particular expertise as to how to really use that medium. To be honest and fair, it’s probably kind of hit and miss.

Mettler: From my viewpoint, a studio Police track like “Secret Journey” [from 1981's Ghost in the Machine] would be an amazing thing to hear in surround, considering all the subtleties and nuances in it.

Copeland: Yeah. Well, there is a world of audiophiles out there. But my kids, they don’t care about quality. Whatever comes out of their laptop speakers is just fine for them. And there’s something important there, and that is: it’s the music, not just the audio. I remember with Sgt. Pepper — I’m showing my age here — I heard it on the radio, and it sounded great. But the first time I got the album home, and somebody had stereophonic sound, you listened to it with the lights out, and holy moly, what a new experience that was!

Mettler: Do you still like the vinyl medium?

Copeland: I like the sound of it, but I’m much more enamored with the sound of valve amplifiers. And that’s not because they’re accurate, or anything like that — there’s a sound, like an aroma. It’s a form of distortion, in fact, but it has associations that are good associations, and that pumping sound out of a valve amplifier is just a beautiful thing. You don’t really think of it until you turn on an old tube radio, and it just pumps in a cool kind of way.

I’m told by the people who know that that groove in the vinyl has higher resolution than 64k digital, and if you say so… Well, as you know, I’ve lived through several technologies of recording. When I first started, 8-track was a big deal. Then it was 16-track, and it was like, “Oh my God, what are we going to do with all these tracks?” Then it was 24, and then they invented slave reels, and it was unlimited. Then the first Mitsubishi rolled into the studio — digital! Unlimited! 48 tracks! Every time you bounced tracks, you didn’t lose anything. And it went on and on and on. From there, they invented computers — which sounds like I’m joking, but no. They invented computers that were available and smaller than a house.

So that’s three generations right there that audio has gone through, and I’m not that sentimental. I love the sound of a valve amplifier, but you cannot persuade me to go back to an old Studer 24-track — no way, no how. There’s an app for that. That love people have for the way drums slap the tape, you know, the sound you get from that, which is overloading the tape — there’s an app for that, and a pretty convincing app. Meanwhile, I’m not getting out the scissors and cutting that 2-inch tape and carrying around those slave reels — no way, no how. I’m ProTools!

Mettler: So no more razor blades for you, Stewart?

Copeland: No more! Never! I say that having lived through the hell of that Paleolithic era of recording. I’m real happy with modern recording techniques. Because that allows me to concentrate of making cool music, and getting to that cool figure that I want. I can cut straight to the chase of making new music without the technology that has interesting colors but slows the process down.

Mettler: The precision of your snare drum sound has always been a hallmark. Is that something you feel you can capture better now with new technology?

Copeland: No, what I can capture now better is what I’m doing with the snare drum and how I play the snare drum: Getting a good take of me banging on the snare drum can be done much more easily than getting a take on tape. In other words, I can hit that snare drum better with modern technology. Maybe the sound that gets recorded we can argue about whether it’s as good or not. I think it’s pretty good.

Mettler: Dou you still have the same snare from back in the day?

Copeland: Yes, I’ve still got the snare drum I used for all of those recordings right here in my studio, right in my drum set. I’ve got a really romantic name for it: Snare. Sing songs about… [pauses] The Snare. It is a really great drum. It’s kind of a fluke. I’ve had it cloned. My drum company, Tama, has rebuilt that snare drum — the metallurgy, the amount of brass, everything — so I’ve actually got five of them now. But the one on my drum set is the one.

Mettler: Where did you find it?

Copeland: I don’t even know how it got into my collection. Just one day, it was my snare drum, and neither I nor my tech can remember where it first appeared.

Mettler: What makes that snare so special?

Copeland: The thing about it was, I just tuned it really high. It was in an era where the old wave was just going out and the producers would talk about getting a “fatback.” And I’d say, “Fatback? Uhh, what am I gonna do with a fatback?” I remember recording my first album in the ’70s, and the record company threw it out and went and got some new producers to record it “right.” Well, they kicked me out of the studio for a few hours while they got “my” drum sound. They tuned the drums and miked them up. “Ok, they’re sounding great, so now you can play.” And they sounded awful. It was a fatback: [makes thudding noises]. Oh God, dead drums. That was the fashion of the day. So when I had my own band, The Police, I could tune myself. I knew what drums should sound like, and it ain’t that! At the time — it’s not such a big deal now — but at the time, that high-pitched, cracking snare drum was way out of line.

Mettler: What would be the first recorded example where you felt, “Yeah, I totally got it right”? The way it should be?

Copeland: I think the second Police album is my favorite-sounding album. That would be Regatta de Blanc [1979].

Mettler: Can’t argue with that. One of my favorite recorded moments of yours is the hi-hat performance on Peter Gabriel’s “Red Rain” [on 1986’s So]. How did that come about?

Copeland: Ah yes. [chuckles] Well, he called up. We knew each other socially, and I was mentioning how I was trying to figure out other ways how to supply the 16th notes in any given song. And the reason we were talking was he already had the same epiphany: “How about I tell the drummer he gets no cymbals?” I was telling him about other things I used like pots and pans, and he said, “Well, come on down and give me some of that!”

So I did! When I went down to his studio there in Bath [Ashcombe Studios], I wasn’t playing on the record, but just on some very weird, vague kind of riffs that he had going. He had Tony Levin in there on bass and a couple other musicians, and we were just kind of screwing around, and later — a long time later — I didn’t recognize any of the songs, because I hadn’t heard any of the songs until the record came out! All I heard was just us doing riffs and grooves, which he cut up and later added lyrics to and wrote songs around, and added chords and actual music. And so, it’s odd. Which tracks did I play on on that album? I’m not even sure! Am I even in there? Peter says so. Ok, I’ll take the credit. I’ve got a platinum album from it, so I guess it was my hi-hat.

Mettler: So is one of the best-sounding recordings from the ’80s.

Copeland: Peter’s a real audiophile. He is really into recording techniques, and just getting it to really sizzle. I’m in too much of a hurry for that, so I’ve been working my entire career with Jeff Seitz for that stuff. It’s a symbiotic relationship. I just breeze on through, but I gotta make it sound good Nowadays. I’m a one-man show in here. Jeff, my engineer, is one of my closest, longest friends, but it’s pretty much social now. Once again, with technology, I’m just in here, and I go straight to it. Click-click-click on the alphanumeric, and I don’t even need any intermediaries anymore.

Mettler: I talked to Andy Summers recently about his new band, the Circa Zero project —

Copeland: It’s pretty good! Ol’ Andy’s raging on the guitar! I love hearing that!

Mettler: He even joked that if The Police ever did another tour, it would probably be a Las Vegas show.

Copeland: Oh, I love the sound of that! Hopefully by such a time, decades from now, Pearl Jam will be playing Vegas, and it’ll be cool. That would be so sweet to roll out of your swank hotel room and go right down to the stage. It’s the fun part of playing without the un-fun part, which is the travel. Going through airports every day — that’s a pain. Playing the same room every night — that’s what we’re here for! That whole Vegas residency thing — all of us super-hip cats who wouldn’t be caught dead playing Vegas are actually full of envy. Oh yeah, book me a flight for Vegas! I’m not sure it’s the right thing for The Police to be doing, but it sounds like a sweet gig.

Mettler: Will The Police be doing anything else?

Copeland: No, I don’t think so.

Mettler: You’ve put the lid on it?

Copeland: Yeah, with the best of intentions. We’re all pretty busy.

Mettler: Well, good luck with Ben-Hur. And to think you owe it all to Francis Ford Coppola. [Coppola asked Copeland to score his 1983 film, Rumble Fish.]

Copeland: Yes! Dear Uncle Francis, this is what you wrought! All your fault. He’s always been very supportive. He saw Oysterhead, he came to the San Francisco Ballet. I’m very proud to have him as a mentor.

Mettler: Last question: What’s the future of music delivery, as you see it?

Copeland: The music will be an implant, inside your brain. They’ll just inject it in one ear with a syringe, and presto!

]]>The bottom end has never been quite the same since Jack Bruce picked up his first bass over 6 decades ago. The vaunted Cream bassist wrote the book on the art of the low-end hook, as his syncopated approach to playing bass helped shift pop music’s bottom-end emphasis away from just laying down root notes and fifths, in turn opening the door to a more adventurous yet melodically inclined style that laid the foundation for the rock explosion of the ’60s. Turns in both Manfred Mann and John Mayall’s bands set the table for Bruce to connect with Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker and forge Cream, wherein the super Scotsman set the heavy-blues power-trio standard with epic runs and full-band interplay in songs like “I Feel Free,” “Spoonful,” “Politician,” and “Sunshine of Your Love.”

Once Cream curdled, Bruce delved further into ... Read More »]]>

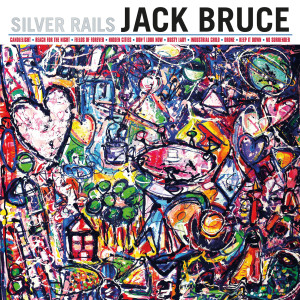

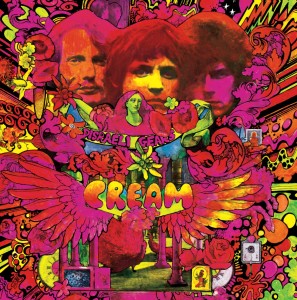

The bottom end has never been quite the same since Jack Bruce picked up his first bass over 6 decades ago. The vaunted Cream bassist wrote the book on the art of the low-end hook, as his syncopated approach to playing bass helped shift pop music’s bottom-end emphasis away from just laying down root notes and fifths, in turn opening the door to a more adventurous yet melodically inclined style that laid the foundation for the rock explosion of the ’60s. Turns in both Manfred Mann and John Mayall’s bands set the table for Bruce to connect with Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker and forge Cream, wherein the super Scotsman set the heavy-blues power-trio standard with epic runs and full-band interplay in songs like “I Feel Free,” “Spoonful,” “Politician,” and “Sunshine of Your Love.”

Once Cream curdled, Bruce delved further into flexing his compositional and jazz chops, as evidenced by his 1970 free-form fusion precursor Things We Like and 2012’s improv-driven, self-titled group tribute to late jazz drummer Tony Williams, Spectrum Road. Silver Rails, his first solo studio effort in 10 years, brings his career-long broad genre explorations under one roof, and it’s packed with primo Jack: the brooding, confessional “Reach for the Night,” the heartfelt piano ballad “Industrial Child,” and the pummeling, deep fuzz of the aptly named “Drone.” Here, Bruce, 70, and I discuss how Rails got on track, cutting sides at Abbey Road Studios, and the eau de Cream. One thing’s for absolute sure: Bruce remains the cream of the crop.

Mike Mettler: Tell me what it was like working at Abbey Road Studios when you were making Silver Rails.

Jack Bruce: It was amazing. Studio One there is so huge. They have the greatest microphone collection in the world; so astounding. There’s a whole department where they have guys who just look after the old mikes. So who knows — you might be singing into the same mike that John Lennon sang into. [chuckles]

It has quite a vibe when you’re in there. It definitely feels different. I think all the musicians I had with me brought their games up a notch because of respect for what’s gone on there — not just The Beatles and Pink Floyd, but all the way back to [noted English composer] Sir Edward Elgar.

Mettler: You’d recorded there before, right?

Bruce: Yes, the first time was in 1965 [for The Graham Bond Organisation's The Sound of '65], quite a while ago. [laughs] I’ve been in and out of there over the years, but not quite as much recently.

Mettler: Would you consider Abbey Road to be one of your favorite studios to record in?

Bruce: I would say, today, it’s the greatest studio in the world. Partly because of the rooms, which are iconic, partly because of the ambience, and partly because of the way they look after it all. Most studios nowadays have a lot of downtime because a lot of things are often going wrong. You don’t get that at Abbey Road. All of the people who work there are very enthusiastic and very, very good at their jobs.

Mettler: Agreed. I’ve met a few of them myself, like Guy Massey and Paul Hicks —

Bruce: Paul is great. And I was very lucky to be able to use Rob Cass, who’s an in-house producer. In fact, it was his idea that I go to Abbey Road and make the record there.

Mettler: Were there any special production choices you made specifically because you were at Abbey Road?

Bruce: I wouldn’t exactly say that, but one of the great things about Abbey Road is, if you use Studio Two and Studio Three as I did, there’s such a great selection of grand pianos! [laughs] You don’t think of things like that beforehand, but they’re always perfectly tuned and immaculate. They had a wonderful Bernstein, a Steinway, and an amazing Yamaha that I didn’t even manage to get to put on the album.

Mettler: One of the things I like about the sound of Silver Rails is that I get a sense of the musician interplay in the same room. There’s a lot to be said for recording everybody looking at each other instead of just dubbing everything.

Bruce: There is a lot to be said for that, yes. I like a little bit of both. Sometimes I like to start off a song very minimally and record the guitar, the piano, and the drums together, and then overdub. A song like “Industrial Child” is like that. It was done very much live, and I wouldn’t do it any other way if I could. I love playing with incredible musicians like that. I wouldn’t want them to just send me a wav file. There’s none of that going on here.

Mettler: Besides “Industrial Child,” do you have any favorite moments for you behind the piano?

Bruce: I think “Hidden Cities,” because that was such a challenge. It was challenging music. Here’s a very strange story that I’ll tell you. When I was very ill about 10 years ago [Bruce had a liver transplant in 2003], I was in an induced coma for a few weeks, and I started writing all of this music while I was comatose — and I remembered a lot of it. The second, sort of quiet part of that song was one of the things I wrote when I was in that condition. It was like experiencing rising light and sound, and I thought, “How am I going to achieve that? How am I going to realize that in actual, practical, physical music?” I didn’t know if I’d ever be able to replicate that piece of music, but we actually got it fairly quickly, with Cindy [Blackman] Santana on drums and Uli John Roth on guitar. The harmonies were done by a group my daughter put together, called Aruba Red. She put together this amazing group of young women. And it was not the easiest thing to sing. They really went for it, and I’m really proud of them.

Mettler: Wow, that’s amazing you were able to bring that all to life.

Bruce: Quite remarkable, yes.

Mettler: One of my favorite songs has to be “Drone,” which is quite heavy, and basically feels like your Black Sabbath track. Did you play that live in the studio and the overdub it later?

Bruce: I was using my old Gibson EB-1 [violin bass], which has got this incredible sound, almost like a barn door. [both laugh] I used a pedal for the effects, but I don’t even know what it’s called. It was given to me by this guy in Japan — he came up to me at a concert and just handed it to me. It’s an incredible pedal, but it doesn’t even have a name on it or anything.

Mettler: Just call it the JB-1, since it’s now officially your own drone. I also heard some planes ready to crash around me at any moment on there.

Bruce: Yeah, the airplane overdub.

Mettler: In the intro, is that just amp buzz and feedback when you’re starting up?

Bruce: It is, yeah; nothing else. And very good miking. And a little bit of pre-amping is always nice. But you do have to go for separation to a certain extent. It’s a be-all and end-all for me.

Mettler: Another thing I like is that the tonal character of your voice is still fantastic. What’s the secret? How have you been able to maintain it all these years?

Mettler: Another thing I like is that the tonal character of your voice is still fantastic. What’s the secret? How have you been able to maintain it all these years?

Bruce: [laughs] I don’t know! I don’t have any magic thing I do. Well, I was actually a classically trained singer, and I think that helps, since I know which muscles to use, and not. Every style of singing is valid in my book, but if you want to be singing at a certain level for 40 years or more over your lifetime, well, it’s a good idea to know about how to use those muscles.

Mettler: Since you continue to play live, we the audience still want to hear those qualities in your voice, especially when you sing falsetto and the more delicate parts.

Bruce: There is an almost falsetto, “head” voice that I use, and always have, especially with Cream. On “I Feel Free,” for instance, I used that head voice.

Mettler: And you still play that song live, right?

Bruce: I have done “I Feel Free,” yes. I used to do it when I played with Ringo [Starr, on his recurring All-Starr Band tours]. But normally, I don’t do that [with my solo band] because it needs all of those other vocals, you know. There are a lot of vocals on there, so unless I have a big vocal group, I can’t do it, really.

Mettler: Speaking of Cream, I’ve enjoyed the higher-grade LP reissues of the core catalog. And I have to say “Tales of Brave Ulysses” is one of my favorite Cream tracks to spin on vinyl.

Bruce: I agree, “Ulysses” is great on vinyl. I think “I Feel Free” could still be vastly improved — that one was recorded quite badly. It might be nice to tinker with that someday, but I don’t think the master tapes exist anymore. I think a lot of them were destroyed in a fire in Holland.

Mettler: That’s a shame. Well, I do think “Sunshine of Your Love” sounds as vibrant as ever on LP.

Bruce: I still enjoy all those songs, really. I play very different versions of them now.

Mettler: How do you rearrange a song like “Sunshine“?

Bruce: My touring band at the moment is an 8-piece. I have another bass player so I can play piano some of the time, and I’ve got three great horn players. So it’s great to be able to rearrange “Sunshine” for that group, you know. About a year or so ago [on November 11, 2012], I sat in with Carlos Santana in Las Vegas, and we did his [Guitar Heaven] version of it. [Santana has a recurring residency at the House of Blues at Mandalay Bay in Las Vegas. They played “Spoonful” that night too—The SoundBard]

Mettler: Even today, I think people undervalue the way a song like “White Room” was arranged.

Bruce: And also the way it’s written was quite a little bit different. That’s what I always wanted to do: Write songs that had a little twist in them. And that one wasn’t too off the wall for that band.

Mettler: I got to see one of the Cream reunion shows at Madison Square Garden in New York [on October 26, 2005], and I liked the approach you guys took, which was often different from the original recordings. You must have enjoyed that level of freedom.

Bruce: Yes, thanks. As you mature and get older, you’re going to play things differently. I like to listen to people who are still making vital music — people like Bob Dylan, even if some people don’t seem to like his voice now. I love anything he does. Together Through Life [2009] — that’s a good album.

Mettler: It sure is. As far as I’m concerned, Dylan should keep doing whatever he wants to do as long as he wants to do it.

Bruce: I don’t blame him. You’ve got the right to do that as an artist.

Mettler: And so do you! Ok, let me jog your memory even more. Do you remember the first record you ever bought with your own money?

Bruce: Yeah! The first one was Golden Striker [1957], by The MJQ, The Modern Jazz Quartet. When I was at college, I saw them live, and I went out and bought this EP.

Mettler: That was when you were at the Royal Scottish Academy?

Bruce: Exactly. I tried to bring it in for my professors to listen to, but they didn’t want to know about it. I had gone to see The MJQ in concert, in Glasgow. And I found their bass player, Percy Heath, was very inspirational.

Mettler: So that’s what made you decide to pursue the low end, literally?

Bruce: Yeah, absolutely. I had heard Ray Brown, Percy Heath, and Charles Mingus, of course. And that’s why I fell in love with the double bass.

Mettler: The melodic bass style that people almost take for granted today was really your bailiwick. You set that table.

Bruce: Yeah, that was my deliberate attempt to do that. I wanted to do that because, at that time, I heard James Jamerson [the Motown bassist], and I liked what he was doing, so I wanted to go for that whole melodic style. I used the jazz approach and applied it to bass guitar.

Mettler: While I’ve been enjoying Silver Rails on CD and digitally, I’m very pleased to see that it is coming out on vinyl.

Bruce: It is, yeah, but unfortunately minus “No Surrender” [the last track on the CD version]. We just couldn’t squeeze it on. It would have been a little too much for the sound quality.

Mettler: Is vinyl the format you prefer as a listener?

Bruce: I like vinyl, but then again, I’ve always liked whatever is new. [chuckles] I like the convenience of CDs, I must admit. And obviously, I’ve got a smartphone like everybody else, and hundreds if not thousands of tunes on there as well. It’s quite remarkable what you can have on such a little device.

Mettler: For a record like Silver Rails, considering the amount of detail — the organ interplay with the horns, and a lot of the cymbal work — it seems to me that you’ll get a lot more out of it by listening on vinyl.

Bruce: I totally agree. I love vinyl. I don’t buy new vinyls that much, because I’ve got such a big collection from the ’60s and onwards. I even have some very old pre-vinyl records — you know, the shellac ones, some even from the ’30s and so on. The sound quality of those — I mean, obviously, it’s a bit scratchy, but the way they were able to record in the ’30s is just remarkable, often using only one microphone. I’ve got a [French composer Joseph-Maurice] Ravel piece that’s conducted by him, and some Louis Armstrong Hot Five and Hot Seven sides. The way they did it, just by setting up — the louder you were, the further away you were. I don’t know how they managed that, to get that incredible sound.

Mettler: Any other favorite records you can mention?

Bruce: I like a lot of classical music. There’s a wonderful recording by [Seiji] Ozawa, a Japanese conductor, of the Messiaen Turangalila Symphony [1967] that’s remarkable. There is an argument to be made for both vinyl and digital for classical music. The clarity of digital can be quite useful, but sometimes it can be quite, quite cold.

Mettler: I think having an appreciation for a wide variety of music — classical, jazz, blues, etc. — gives you a broader palette to draw from as a musician. Artists just starting out should take a cue from what you did and go all the way back to the source.

Bruce: They may think going all the way back means going back to Led Zeppelin, or something. Or Cream. [both laugh] Worth checking things out a bit further back than us, I think.

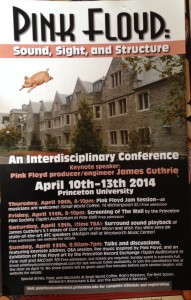

]]>Pink Floyd and music academia don’t usually mix. But that didn’t deter Gilad Cohen and Dave Molk from organizing the amazing “Pink Floyd: Sound, Sight, and Structure — Interdisciplinary Conference,” the first ever academic conference devoted to the mighty Floyd at Princeton University on April 10-13. In addition to scholarly discussions and live music, the linchpin was a three-album surround-sound listening session shepherded by Pink Floyd producer James Guthrie on Saturday and his keynote address on Sunday.

I was generously given the central sweet spot seat in the third row for Saturday’s surround-sound sessions at McAlpin Hall at Woolworth Music Center. First up was the world premiere of the 5.1 version of Roger Waters’ 1992 opus, Amused to Death, which was mixed by the symposium’s guest of honor, James Guthrie, the man who’s handled the direction of The Floyd’s sonic legacy since 1979′s The Wall. ... Read More »]]>

Pink Floyd and music academia don’t usually mix. But that didn’t deter Gilad Cohen and Dave Molk from organizing the amazing “Pink Floyd: Sound, Sight, and Structure — Interdisciplinary Conference,” the first ever academic conference devoted to the mighty Floyd at Princeton University on April 10-13. In addition to scholarly discussions and live music, the linchpin was a three-album surround-sound listening session shepherded by Pink Floyd producer James Guthrie on Saturday and his keynote address on Sunday.

I was generously given the central sweet spot seat in the third row for Saturday’s surround-sound sessions at McAlpin Hall at Woolworth Music Center. First up was the world premiere of the 5.1 version of Roger Waters’ 1992 opus, Amused to Death, which was mixed by the symposium’s guest of honor, James Guthrie, the man who’s handled the direction of The Floyd’s sonic legacy since 1979′s The Wall. Amused will be made available on multichannel SACD and 200-gram double vinyl from Analogue Productions. I haven’t seen an official release date from my sources at Columbia/Legacy (Roger’s main label) as I write this, but it may be out by September. Also, the fine folks at Acoustic Sounds are deeply involved with the release and specs of this important project, so stay tuned for updates.

Anyway, back to the listening details. After Amused, we got to hear the SACD 5.1 mixes of The Dark Side of the Moon and Wish You Were Here. (The entire three-album 5.1 playback was then repeated for an evening session.) The SACDs were cued up by assistant engineer Joel Plante on an all-purpose Oppo player, and all of the music was played back through a full surround array of quite formidable ATC Professional Series monitors and a pair of ATC subwoofers.

But before Plante cued up Amused 5.1, Guthrie spent a few minutes explaining how the mix came to pass. He admitted Amused was the most complicated stereo mix he had worked on when it was first released, and that gathering all of the sonic and sound-effects elements to “rebuild it from scratch” for the new stereo and 5.1 mixes was a daunting process. When he explained the importance of doing Amused in surround sound to Waters, Guthrie said he told Roger that it wasn’t about making money, but that “he had to look at it as an investment in his art.”

Careful With That Axe: Waters on stage. Photo by and copyright Jill Furmanovsky, courtesy Capitol Records Archives and rockarchive.com.

And what an investment it is. The Amused 5.1 mix was as wide, tall, and ambitious as the music itself. Even on first listen, it was clear the amount of detail instantly evident would reveal even more depth and layers upon further review. The full-channel female chorus on “What God Wants, Part I,” the character of Roger’s impassioned, high-centered lead vocals on “Perfect Sense, Part II,” and the dramatic echo-to-fade drum hit that both opens and closes “The Bravery of Being Out of Range” were immediate highlights. Most of the album’s TV/audio chatter emanated from the rear left channel, though some did appear in the rear right as well (but only some). The swooping plane in “Late Home Tonight, Part I” moved from right to left before its super-low-end denouement rumble jarred the room. Jeff Beck’s masterful guitar solo on “What God Wants, Part III” started in the center channel before panning to all all-channel, patented Becko-warble assault.

After the all-channel nature sounds of the title track — a callback to what was heard in the very first track, “The Ballad of Bill Hubbard” — faded away and the gathered audience applauded vigorously, Guthrie observed, “He’s a clever boy, that one.” Couldn’t agree more. Programming note: Once some of the dust settles and we get closer to the actual release date for Amused to Death 5.1, Guthrie, Plante, and I will be discussing the ins and outs of this groundbreaking mix, as well as other Pink Floyd 5.1 recording minutiae, right here on SoundBard, so keep your eyes peeled.

At Sunday’s keynote held upstairs in room 10 at McCosh Hall, Guthire shared a number of amusing and enlightening stories about his career as a producer, working on The Wall both studio and live, recreating “Money” for 1981′s A Collection of Great Dance Songs with a Linn drum-machine track later added to by Nick Mason, swapping the flight-check sequence on “Learning to Fly” with dialogue from Airplane! as a joke for David Gilmour, and so much more.

Guthrie also shared some great advice for budding producers and engineers, advice that all music lovers should take to heart: “Learn how to listen, and learn how to trust your ears.” He championed what I like to refer to as the “personal investment” in listening — that he wants to be transported and taken on a journey by an album or a piece of music. (Me too.) Guthrie summed things up by borrowing a line his wife shared with him from the French poet Baudelaire, imploring us to “be drunk with fascination” and follow our passions, since “passion is infectious.” He concluded by pointing out that being creative and following/sharing those passions get you that much closer to the source. Yeah, I can get behind all of that.

During the Q&A portion, Guthrie confirmed he’d like to do more Pink Floyd 5.1 mixes, but that it often comes down to a matter of the time available on his and the band’s collective schedules, so “don’t hold your breath.” That said, he was willing to concede that The Wall seems to be the most likely next candidate in the 5.1 queue, but the album he’d be most interested to do in surround is Animals. When I interviewed Grand Vizier/drummer Nick Mason about the Immersion box sets, live quad, and surround sound back in 2011, I suggested that Meddle would be a good 5.1 candidate, as I’d love to hear “Echoes” in surround. Mason replied, “I think it would be great to do those, yes. Funnily enough, I’ll tell you the other one I’d like to see: A Saucerful of Secrets. There’s some great stuff on that. ‘Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun’ would be great in surround, wouldn’t it?” Can’t meddle with any of that logic. (I’ll be sure to nudge Guthrie politely/accordingly about all of these options when he and I next speak, don’t worry.)

Take it from a true Pink Floyd aficionado: The Interdiscplinary Conference was a rousing success — nothing but high fidelity, first class the whole way. Wot’s next, lads?

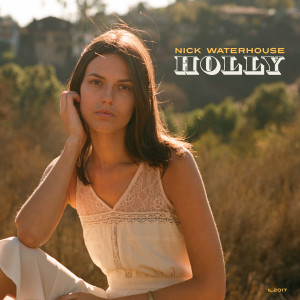

]]>Call him The King of Retro Cool. You may have seen Nick Waterhouse wondering “where you think you’re gonna go/when your time’s all gone?” in the current Lexus CT Hybrid “Live a Full Life” commercial campaign, but his super-snazzy brand of modern jazzabilly rock extends well beyond that 30-second snippet. His second full-length LP, Holly (Innovative Leisure), builds on the retro-rockin’ bed of 2011′s Time’s All Gone. Waterhouse and I recently convened to talk about Holly‘s sonic merits, his favorite vinyl reissues, his playback gear, and the benefits of recording in mono.

Mike Mettler: Was Holly recorded direct to tape?

Nick Waterhouse: It was! I did the record at Fairfax in Van Nuys, [California], which is where the Sound City studios used to be. Kevin Augunas was my co-producer on the record. We used four Scully 16-track recorders gotten from A&M Studios, so they’re really ... Read More »]]>

Call him The King of Retro Cool. You may have seen Nick Waterhouse wondering “where you think you’re gonna go/when your time’s all gone?” in the current Lexus CT Hybrid “Live a Full Life” commercial campaign, but his super-snazzy brand of modern jazzabilly rock extends well beyond that 30-second snippet. His second full-length LP, Holly (Innovative Leisure), builds on the retro-rockin’ bed of 2011′s Time’s All Gone. Waterhouse and I recently convened to talk about Holly‘s sonic merits, his favorite vinyl reissues, his playback gear, and the benefits of recording in mono.

Mike Mettler: Was Holly recorded direct to tape?

Nick Waterhouse: It was! I did the record at Fairfax in Van Nuys, [California], which is where the Sound City studios used to be. Kevin Augunas was my co-producer on the record. We used four Scully 16-track recorders gotten from A&M Studios, so they’re really nice. And I feel it imported a lot of that character, because Scullys are known to be precise and have a kind of different warmth than Ampexes do. I was so pleased with the results.

Mettler: I really got a sense of the character of the room and space you recorded in, because Holly has that special, live off-the-floor feel.

Waterhouse: Oh yeah yeah yeah! I’m a big advocate of cutting live. A lot of this record was tracked with the keys, rhythm guitar, bass, and drums all together.

Mettler: On a song like “Well It’s Fine,” you really hear the subtlety and detail with [Richard Gowen's] brush drums on the intro.

Waterhouse: That tune was a favorite of mine, even though it’s the most minimal. You can hear so much of the room, and everything was cut live. Listening back to it gave me the chills. It reminded me a lot of the [Rudy] Van Gelder productions for the Blue Note jazz stuff.

Mettler: It’s all got that cool, early-’60s, everybody-is-looking-at-each-other feel. And I love the sax solo on “Dead Room” —

Waterhouse: Mm-hmm, that’s the very talented Jason Freese on tenor sax.

Mettler: “This Is the Game” has some sweet horns in the intro and then that nice organ interplay in the middle. Everything sounds so good digitally, so it begs the question: How good does this album sound on vinyl?

Waterhouse: You’ll love it! I’m very excited. I had the very talented Kevin Gray master it, and had Quality Record Pressings in Salina, Kansas press the record. As you probably know, they did Quality Pressings of some of the Prestige and Blue Note stuff.

Mettler: Oh yeah, that’s as prime as it gets.

Waterhouse: They cut it on the same machine that they do their deep-groove reissues with. Holly is 180-gram on a single disc, at 33. I stayed conservative in that sense. I’m really pleased, because the record clocks in at 31 minutes.

Mettler: That’s nice, so you didn’t have to make any compromises at all on either side.

Waterhouse: Not at all. I’m really excited how “Sleepin’ Pills” ends the groove of Side 1.

Mettler: Man, I have to get a copy ASAP. You must have etched something into the runout groove, too.

Waterhouse: Oh yeah, there’s always a little message there.

Mettler: What kind of turntable do you have?

Waterhouse: I have one of those old VPI Classics that I really like a lot. I used to have an Empire 298 that I really liked, and I actually moved that to my office at the studio. I picked up the VPI secondhand last year, with my first big recording check. I figured that was the best way to reward myself. [both laugh] And that goes through a nice Fisher X-101-B receiver. I like the phono stage on that a lot.

Mettler: What kind of speakers do you run through?

Waterhouse: Klipsch Heresys. To me, that’s a very classic high-level consumer system. Most of what I listen to are mono jazz LPs and pop 45s.

Mettler: What kind of cartridge does the VPI have?

Waterhouse: I actually switched between a Denon DL-102 and DL-103. I have the 103 because that thing takes beat-up old 45s really well.

Mettler: What’s your current favorite record that you’re spinning on the VPI?

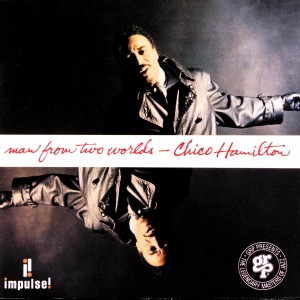

Waterhouse: Oh, man… well, I’m a massive fan of Chico Hamilton’s Man From Two Worlds (1964), on Impulse! That’s slightly off the beaten path, but —

Mettler: Somebody I talked to last year also recommended a Chico record… let me think for a minute [pauses]… oh yeah! It was Derek Trucks, when he called me from the side of the road. That’s totally in his blood.

Waterhouse: Oh yeah, there’s a lot of heavy jazz in his playing.

Mettler: The Dealer (1966) was the Chico record he was talking about.

Waterhouse: Oh, The Dealer is really tough! I love that record; it’s a funky record. Man From Two Worlds is more my speed, though. Derek Trucks is a little more funky than I am as a player. [chuckles]

Mettler: Smoky cool is what I’d call your kind of playing. What else can you recommend?

Waterhouse: I’m also a really big fan of Garnet Mimms, and he has two records out on United Artists. “Cry Baby” is the single [later covered by Janis Joplin], but As Long As I Have You (1964) is one of my favorite LPs of all time. It’s a really wonderful-sounding, big city, kind of New York-full kind of record with Gerry Ragovoy production. And of course, you can’t go wrong with Bobby “Blue” Bland’s Two Steps From the Blues (1961), on Duke. It’s an amazing-sounding record — and in mono, nonetheless.

Mettler: You released your first album, Time’s All Gone, in mono, right?

Waterhouse: Yeah. All my 45s are in mono, and believe it or not, Holly is in mono too. It’s funny, because I remember sitting with the mastering engineer, and he asked me three times, “This is mono??” It was great!

I come from a background of wanting to learn how to do it myself — the process of how to make the records. I had read a lot of books and interviews about engineering and recording. I never went to engineering school, but they say they teach you how to mix in mono first because if you mess up a mono mix, you mess up the whole thing, but you could squeak by in a stereo mix. But I just stop there, I don’t go any further than that statement. [laughs]

Mettler: Do you remember the first record you bought as a kid, before you worked in the record store? [Waterhouse worked at Rooky Ricardo’s Records in the Lower Haight in San Francisco when he was attending San Francisco State University.]

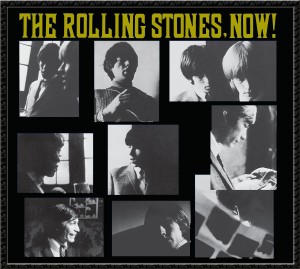

Waterhouse: It’s funny. There’s a series of records I didn’t put any cash down for but that my uncle gave me. It was three of the earliest Rolling Stones records: The Rolling Stones Now! (1965), Out of Our Heads (1965), and Aftermath (1966). He gave me the London pressings of those. And on top of that, he gave me a couple of Miracles, Four Tops, and a Yardbirds American reissue… what was it called…?

Mettler: It was probably the Yardbirds Greatest Hits (1967), with the “lasso” song logo on the cover, and the LP had that yellow Epic label on it. Had that one in college myself. My Dad also gave me his copy, which didn’t have the outer sleeve.

Waterhouse: Yeah, that’s it! Those records were all big parts of my life. But the first things I bought were not LPs, but two 45s: Booker T. & the M.G.’s’ “Green Onions,” and Charlie Rich’s “Mohair Sam.” Those I see as the cornerstones of my musical vocabulary, really.

Mettler: Please tell me you still have those 45s.

Waterhouse: I do, yeah! They’re in the boxes, so to speak. When I finally became a real musician, I explained to my mom that all those years spent scolding me for spending my day-job money on records was moot now.

Mettler: I love that! How do you stand in the Beatles universe in terms of mono vs. stereo?

Waterhouse: Oh, I have no opinion about that — Ray Charles was my Beatles.

Mettler: Ok, then what about The Rat Pack?

Waterhouse: Oh, The Rat Pack. I dig them, but I never got too heavy into them. I love their records in mono because that’s how they were recorded, in that format.

Mettler: Anything else on vinyl that you took a chance on that was great?

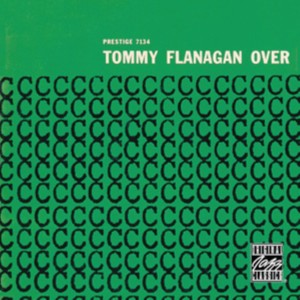

Waterhouse: Let’s see, I’m looking at my wall right now… I just got a really amazing Japanese reissue of Georgie Fame: Rhythm and Blues at the Flamingo (1964), a live record. It’s really nice, a replication of the U.K. pressing. They did a great job remastering it. I’ve got the new Charles Bradley LP here, Victim of Love (2013), which sounds really nice, and I just invested in a subscription to the Prestige Mono LPs Reissues Series, and they just sent me Phil Woods Quartet: Woodlore (1955), Hank Mobley: Mobley’s Message (1956), and Tommy Flanagan: Overseas (1957). I’m really enjoying those right now.

Mettler: Last thing: Bob Dylan. Does he filter into your universe?

Waterhouse: He does, but he came in really late. I feel grateful, actually. I like that he came in after I learned about blues, R&B, folk, and gospel, because now I see all that in there. I love him in mono, especially what’s in The Complete Mono Recordings box set. Here’s a little trivia you’ll enjoy: The console that’s now at Fairfax is the one Kevin Augunas, the owner, got from Bradley Barn, the old RCA studio in Nashville. It was built in 1965, and it might have been used to track Blonde on Blonde. How cool is that?

]]>Richard X. Heyman is a rock & roll lifer. I first became exposed to his indelible brand of garage pop on his 1990 solo album Living Room!! (Cypress), instantly falling for the hooks of “Union County Line” and “Local Paper.” (And, yes, I do have it on vinyl, folks.) Soon thereafter, I learned of his pioneering role in nearby Plainfield, New Jersey’s ’60s garage rockers The Doughboys, who continue performing live and releasing top-notch music to this day. (“Black Sheep,” “Why Can’t She See Me?,”“It’s a Crying Shame,” and “YOYO” are but four of my favorite modern-era Doughboys tracks.)