BY MIKE METTLER — MARCH 12, 2015

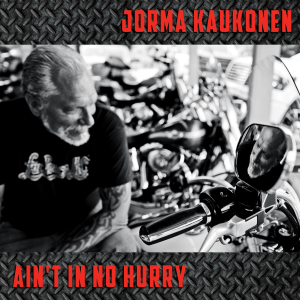

To modify a phrase, fingerpicking guitar maestro Jorma Kaukonen just keeps on innovatin’. For over a half-century, Kaukonen has followed his own path and applied his folk roots to variations on psychedelia with Jefferson Airplane and free-form blues with Hot Tuna, not to mention his own solo rock and unplugged outings. On his acoustic-driven new disc, Ain’t In No Hurry (Red House), Kaukonen continues to push forward on tasty, intense tracks like the hopeful timelessness of “In My Dreams,” the traditional riches-to-rags lament of “Brother Can You Spare a Dime,” and the down-home grit of “The Terrible Operation.” Observes Kaukonen, “One of the cool things about the way the album is mixed is that there’s this magnificent, transparent presence of all the instruments, no matter who’s playing and where they are. You can hear them all; they’re there.”

Kaukonen, 74, and I got on the phone recently to discuss his recording techniques, his mastery of Drop D tuning on an iconic song, and the hi-fi gear that’s served to enhance listening experiences all throughout his life. The man may not be in a hurry, but he sure is getting somewhere.

Mike Mettler: I really like the sound quality of this recording. Did you guys cut everything together in the same room, with everybody interacting and looking at each other while you played?

Jorma Kaukonen: We did. We recorded this on the Fur Piece stage, at my theater at the Fur Peace Ranch [in Meigs County, Ohio]. And I got Justin Guip to engineer and mix it, and Larry Campbell to produce it. They also play on it. Larry’s partnership with Justin, who is also our drummer in Hot Tuna and the drummer on Hurry, is something, and so are Justin’s Americana sensibilities — he just knows how to make stuff sound great. He did all those Levon [Helm] records too.

[Guip played drums in the Levon Helm Band from 2004–2012, was production manager for Helm’s Midnight Rambles, and served as senior recording/mix engineer at Levon Helm’s Recording Studio in Woodstock, New York. Campbell was the musical director of the Midnight Rambles, and he and Guip continue to work together as a formidable Grammy Award-winning production team. Helm, who passed away in 2012, appeared on Kaukonen’s 2009 release, River of Time.]

Mettler: You made some interesting choices in terms of stereo separation on certain tracks where [mandolin player] Barry Mitterhoff is in the left channel, and you’re in the right one.

Kaukonen: You know, it’s funny. I listened to my CD on my tube stereo yesterday, and yeah, Barry and I are left and right on “Brother Can You Spare a Dime.” One of the things I noticed — and I was stringing guitars when I was doing this, not like I’d be listening in the old days where you just shut everybody up and did nothing but listen — but one of the cool things about the way Justin mixed this album is that there’s this magnificent, transparent presence of all the instruments, no matter who’s playing and where they are. You can hear them all; they’re there. I would never have deigned to want to mix one of my own records because I just don’t have those kind of sensibilities, but when I listen to this stuff, it just sounds live to me, which is cool.

I’ve got a 17-year-old son, and I don’t know if he’s ever going to get his own stereo. He just listens to mine or he listens to stuff on headphones that aren’t ultra hi-fi, though I did give him some studio headphones recently. At the risk of sounding like the old guy that I am, many of the kids just don’t listen to the recordings like the way we did when we were younger, when you just bathed yourself in that stuff.

Mettler: I know. I call it appointment listening, which is what I do when I go down to my listening room with no phone, no texting, and no distractions. It’s all about the listening.

Kaukonen: I like that — appointment listening. I’m going to write that down. I’m going to do that; no messing around.

Mettler: And no charge for using the phrase. Tell me more about your stereo gear.

Kaukonen: Ok, well, you’re going to love this. I have a couple of turntables — a Thorens and a Denon, plus one that you use to digitize records. I’ve got a 20-year-old high-performance Sony CD player that plays CDs the way it was meant to be. My amps — now we’re talking. I’ve got a Marantz preamp, and I have an Michaelson & Austin valve tube amp. The last time I put new tubes in it 20 years ago, it cost me about a thousand dollars. I’m using Polk Audio speakers I got from my dad, but when I feel like listening to rock and roll the old way, I put on the JBL 4312s [studio monitors].

Mettler: I approve! That’s totally the way to go.

Kaukonen: It really is. I’ve got a turntable, but how often do I listen to it? Honestly, not that often, because CDs are so convenient. But I never got rid of my vinyl collection, and when I do want to listen to it, I’m ready to go.

You obviously will be able to relate to this. When you sit down for your, what did you call it, appointment listening — there’s one place you can do that in the room, the sweet spot. I listen to stuff with my wife, who isn’t as obsessively tuned into it as we are, and having our two chairs next to each other is not good. They have to be lined up front to back.

Mettler: Yeah, that’s the way it’s gotta be done. Some of your live recordings are available in 24-bit on HDtracks — you must like that, considering the subtleties and detail related to how you fingerpick.

Kaukonen: Anything at 24-bit is happening. I don’t download, because I live in an area that has moderate download speeds. But my guys, like Jason, are totally into this stuff; you’d love having a conversation with them. They tell me we have to do this because guys like us will love it, so I go, “Rock on.”

Mettler: I think the style you have as a player comes across better in hi-res because you get more of the feel and that sense of interactivity between the players. We can hear what you’re doing together on that Fur Peace Ranch stage. Like on “The Terrible Operation,” it sounds like you guys are switched, in that Barry was in the right channel and the solo in the left was you.

Kaukonen: Right. Actually, in “The Terrible Operation,” Barry is not playing on that one; Larry is. You know, I’ve never discussed it with the guys, but everything is thought out, as you know. Things don’t just happen by accident, just so that it is quite possible guys like you will notice. (both laugh)

Mettler: Oh yeah, I notice. What was the first record that had an impact on you when you were growing up?

Kaukonen: Ooh boy. Well, let’s see. When I was growing up, my dad had a hi-fi. I didn’t use the word stereo there because it was still mono then. His speakers took up the whole corner of the room — Tannoy 15-inch dual concentrics. And he had a Garrard [turntable], of course. I’m trying to think of the amplifier. It wasn’t components; it was a preamp and an amp — and tube, obviously.

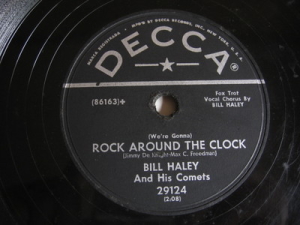

My dad listened to all this classical music. But as rock and roll and the pop thing were happening, the first record that made an impact on me was a 78 of Bill Haley [and His Comets]’s “Rock Around the Clock.” I was just a young teenager when that happened. [“Rock Around the Clock” was released on the Decca label in 1954.]

The first record that I bought, gosh, my my my… it could have been Buddy Holly. Then I started to buy some albums like the Chess series, The Best of Muddy Waters (1958), Howlin’ Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson; all those great cuts.

And I started to buy 45s like we all did. Chuck Berry obviously made a huge impact on us from the guitar-player point of view, because when you look at it, all of us who play the guitar think about all of those Chuck Berry licks that started to define our lives. But really, they’re just like vignettes, like B.B. King, between verses; they’re not wailing all the time like guitar players do today. But Chuck Berry — a folk poet of our time, talking about adolescent frustration — we loved it.

And my father, I remember him saying, “I don’t want you playing any of that crap on my hi-fi. You’ll ruin it.” Well, when he went out of the house, we would just crank it up on that Tannoy concentric, and let me tell you, even in my memory, this many years later — it rocked.

Mettler: And that’s when you were growing up in the Washington, DC area?

Kaukonen: Yeah. My dad worked for the government, and we were stationed a lot of places. When I first heard “Rock Around the Clock,” we were stationed in Pakistan [in Karachi]. Albums were just starting to happen back at home, but we weren’t getting them there. We were maybe a year or two behind the times over there. The stuff would come in through the Armed Forces Radio. It was a little bit behind the times, but nonetheless powerful.

I came back from Pakistan in ’56, we sailed back right after the the Andrea Doria was hit by the Stockholm and sank outside of New York [on July 25, 1956]. We were on the Giulio Cesare, the sister ship, a week or so later. The music on the ship was everything that was happening during the 3 years I had been gone, finding out what I’d missed.

Mettler: A crash course on the sea, basically.

Kaukonen: Totally.

Mettler: Being over there in Pakistan exposed you to all sorts of worldly sounds, which gave you a broader taste.

Kaukonen: Yeah. Of course, we never gave it a second thought at the time, but you’d hear all kinds of things. We heard the sitar, tablas, and all that kind of stuff. I don’t think we realized at the time how cool it was. It’s the greatest.

Mettler: Back to the digital age. What type of equipment did you use to record Ain’t in No Hurry?

Kaukonen: It’s Justin’s stuff. He just built a studio up in his house in Red Hook, [New York], on the Hudson River, but he brought all his stuff here to the Ranch — it was like a studio in a van. He has a huge collection of great microphones —which is where it all starts, as you know. And then he’s obviously using Pro Tools. He had a small Neve board [a Melboune Console], and he also had a lot of plug-ins. He had vintage equipment like Pultech compressors [EQH2]. I guess the most important thing he had besides his ears and his mike placement is the mikes themselves. Whenever we listen to playback in the studio, I always say, “Boy, I wish the record would sound like that” — but of course it never does.

Mettler: That’s the thing about 96/24 — that’s what it sounds like in that form, the best representation of what you intended when you were playing.

Kaukonen: I do recall back in 2002 when I did that recording for Columbia, Blue Country Heart, we did that on SACD. I still have an SACD player and I thought that SACD sounded great, but it’s a lost format.

Mettler: I have an Oppo universal player [BDP-105], and I still play SACDs on it. Songs on Blue Country Heart like “Blue Railroad Train” and “Tomcat Blues” sound great on SACD.

Kaukonen: I also have Steve Earle’s Guitar Town on SACD, and that sounds fantastic.

Mettler: I love that one too. In terms of microphone placement, did you tell Justin and Larry where you want things placed, or…?

Kaukonen: No, what I talk with them about is, “How do you want me to approach this? How do you want me to hold my guitar?” I’ve been playing long enough, so I can hold a guitar pretty much in any way necessary. And I realized when we worked with Al Schmitt back in the day [as producer on various Jefferson Airplane and Hot Tuna albums] — and unfortunately I wasn’t intellectually tuned into this at the time, but now I am — Al is a master of microphone placement. As it’s been explained to me, I guess the demon in getting sounds not just for recording but also by ear is phase cancellation and phasing problems. What I see is his talent in being able to place microphones where there is none of that, or it’s minimized.

Mettler: He’s a master of figuring out the different fields in a recording too — when there’s something in the front, the middle, or the back. Al’s done some great surround mixing himself.

Kaukonen: Also what I’m aware of is the creation of a sonic landscape where you have various and sundry instruments in whatever range they occupy. Al’s able to put them together in an ensemble so everything can be together.

Mettler: The surround mixes that make you feel like you’re in the middle of the entire recording — that’s what you want as a listener.

Kaukonen: Absolutely.

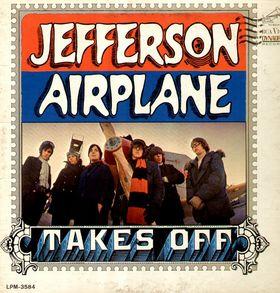

Mettler: Now, the very first Jefferson Airplane record [Jefferson Airplane Takes Off, released August 1966] was done on a 4-track recorder, right?

Kaukonen: It was a 4-track. Dolby, not noise reduction. You actually had to be able to nail your part in order to record it. Don’t get me wrong — we all love the stuff we can do today. But there is something about actually nailing the part.

We just did the show for Jack [Casady]’s birthday [December 13, 2014 at the Beacon Theatre in New York], and we did “White Rabbit” and “Somebody to Love” with Teresa [Williams] singing, and one of the iconic sounds of my solo on “Somebody to Love” is not only the slightly out-of-tunedness of it, but in the bizarre little ending of the “fix,” because if you went any further into it, you’d ruin the track. And that’s how it goes. They didn’t encourage me to do it more than once at all, because more than twice was out of the question. When I hear a band like Grace Potter’s [The Nocturnals] do that song and the guy [Scott Tournet] replicates that, I go, “That’s funny. The mistake has become a part of the song.”

Mettler: We have both mono and stereo versions of Surrealistic Pillow (released February 1967) — do you have a preference?

Kaukonen: Interestingly enough, I think we all loved the idea of stereo because it was so new and so cool, but I do believe in some respect the mono versions have more punch. I’ve got a mono version of an album by an English band called The Move, I don’t know if you remember them —

Mettler: Oh yeah, Jeff Lynne and Roy Wood.

Kaukonen: Yeah, exactly. That record, The Move (1968), is in mono, and it has got punch.

You were talking about 5.1 and 7.1 — I’ve got 5.1 for when we watch movies. But the way I hear things, I don’t like listening to music that way. I do occasionally, but the thing is, I actually have a separate building with my appointment listening room. It’s a two-car garage. I’ve got a shop, and the second story is my office; it’s messy, but that’s where all my stuff is. When I want to do appointment listening, I go out there so I’m not disturbed by anything.

Mettler: 5.1 is an acquired taste for some listeners, and maybe it’s served best by the progressive artists who have classical leanings — groups like Yes and King Crimson, whose music lends itself to that format.

Kaukonen: Right. That makes sense. I get that, absolutely.

Mettler: Although good live recordings in surround can be great if they give you the sense of the space — the arena, the club, the hall. That can take you on an “Embryonic Journey,” if you will.

Kaukonen: So to speak.

Mettler: Speaking of “Embryonic Journey,” you opened up a whole generation to Drop D tuning with that song [from the aforementioned Surrealistic Pillow]. Did you ever think it was going to be that impactful?

Kaukonen: Of course, you never think about that stuff, but that Drop D tuning was so significant for me. My first Drop D song was “Good Shepherd.” I learned it from this guy Roger Perkins. It was ’62 or ’63, and he was playing in San Jose. He showed me the song and the Drop D tuning, and I flipped out. It changed my life in a lot of ways. [Drop D tuning, also known as DADGBE, is an alternate form of guitar tuning in which the lowest (sixth) string is tuned down from the usual, standard E tuning by one whole step, two frets, to D.]

With the advent of the Internet, I tried to track him down a few years ago, and found out he’d passed away [on January 11, 2009, in Claremont, California]. I was working up in Northern California somewhere, and his brother [Bill Perkins] coincidentally came to see me, and I got to tell him, “You know, your brother changed my life when he turned me on to Drop D tuning.”

Mettler: That’s nice. In the middle of psychedelia, just to get a track like that — it gave people more things to discover.

Kaukonen: Yes, it gave people more to discover from me.

Mettler: True. And you’re still playing the Martin M-30, your signature model?

Kaukonen: I am, I am. When we recorded the album, I used the M-30 for a lot of stuff, but not all of it. I also used my old J-50, which was, in fact, the “Embryonic Journey” guitar. There’s no pickup on it, so that guitar is just miked. Speaking of that, in terms of the acoustic instruments on Ain’t in No Hurry, my Martin and the Martin that Larry was playing do have pickups on them. It’s nice to have that sourced for some solidity and some substance, but most of the sound is microphoned.

Mettler: Do you have a different philosophy when you get onstage to replicate Hurry material?

Kaukonen: I don’t think I think about it that way, although the effect might be the same. When I get onstage, like I tell my Fur Peace students, when you plug in an acoustic guitar, in reality, it ceases to be an acoustic guitar, and now it’s large-body electric guitar. So I try to do what I need to do to make it sound as pleasant as possible. And “pleasant” to me means making it sound as acoustic as possible. One of the things that happens anytime you plug a transducer in — like if you’re using a Fishman Aura [Spectrum D.I.], which I use as an intermediate between my guitar and the PA or amp — it picks up the attack transients almost more than anything else. I’ve had to learn how to play lighter so I can get a warmer, more realistic sound out of the guitar, without losing the drive that I’ve learned over the years because I have a very heavy right hand. And over the last decade or so, playing with the newer equipment and gear, I’ve gotten pretty good at it.

For me, I detest monitors. I realize they’re a necessary evil, but I like to do it old school like we did it back in the folk days, when we could hear the sound coming back out of the house. That’s what I like best.

Mettler: That’s the ambience of the room, and also playing off whoever’s there.

Kaukonen: That’s actually as close to what it really sounds like as you can get.

Mettler: Do you have favorites on this record you like to play live? I like how “Bar Room Crystal Ball” is a revival of a classic track.

Kaukonen: It’s really interesting. When we put this together and I sequenced it — I’ve been good about putting setlists together over the years, but to me, each song has a character of its own. Some of them are longer than others, so I’m more fluid with them, “Bar Room Crystal Ball” being one of them. “Brother Can You Spare a Dime,” I’ve been working with that one for years, that’s a good one. That’s just a duet with me and Barry, and I kind of like that also.

“Ain’t in No Hurry” was written by one of our students at the Fur Peace Ranch [Jim Eagan] — my wife heard it and said, “You gotta do this song.” Not only did we do it, but it’s the title track for the album. We’ve got steel guitar on it, and I’m playing acoustic guitar. I do play that song live, and obviously, I’m not going to replicate that stuff and try to recreate the band feeling to it. It’s one of these songs that if you strip the frosting away, the cake is still good.

Mettler: Let’s get more into the art of sequencing. I think that’s a very important part of any record, even if the art of it kind of got lost in the CD age.

Kaukonen: People of our generation — I always listen to the entirety of a record to get the bulk of what it is. That was important to me. I don’t think I was consciously trying to grok what the artists were putting down, but when you listen to The Beatles — their sequencing was always so heady, you know. (chuckles)

I think about it like a set. If I were performing these songs live, how would I do it? I would try to get it where it’s telling a story to the audience. To me, putting a set together or figuring out a sequence is like trying to write a song, because in some way, you’re looking to get a beginning and an end — from front to back, to get that feeling.

Mettler: I think the plot got lost in the digital era of the 80-minute record.

Kaukonen: The other thing is, an 80-minute record is a long record. You’ve really got to be into it to listen to all of it.

Mettler: There are some classic albums of the rock era like [The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s] Electric Ladyland, a double record that may be closer to 60 or 70 minutes [it actually runs 75:47], but still — that’s a sequence of four separate sides with four specific journeys for where Jimi took you.

Kaukonen: It really is. It’s like four different albums in one.

Mettler: Do you have a favorite album or song on that album?

Kaukonen: I think, and so many people feel the same way, “All Along the Watchtower.” After I listen to all four sides, that’s the song I listen to over and over again. He could do just about anything, you know?

Mettler: No doubt about it. And after hearing what he does on Hurry, I think Barry can do just about anything on mandolin.

Kaukonen: Barry plays mandolin on “In My Dreams,” “Bar Room Crystal Ball,” and “Brother Can You Spare a Dime.” The other mandolins on the album are Larry, and when you listen to them, you’ll know the difference. Larry is a great player too, but the touch is different, and the way he handles melody and harmony are different. They are their own people.

Mettler: For a guitar player, it’s really all about the fingers.

Kaukonen: I couldn’t agree more — it’s the man, not the machine. With a piano, you can hear the different touch with different players. The guitar is certainly one of the most personal of instruments.

Like I was telling my students, at this point in my life — the bar has been raised so high since I first started playing. There are fabulous guitar players out there. We could go on about them ad nauseam — and certainly one of the ones to mention is Tommy Emmanuel — but the thing is, there are so many guys who can do so much different stuff. But at this point in my life, the good news is: I only have to sound like me.

Mettler: As someone who’s defined his own style in the fingerpicking universe, we do know when it’s you playing.

Kaukonen: One more thing — do you know the story behind the song, “The Terrible Operation”?

Mettler: No, I don’t, actually. Tell me.

Kaukonen: Well, this is good; you’ll enjoy this. It’s written by Thomas A. Dorsey. He had this record out on Riverside called Georgia Tom and Friends. In the ’20s and early ’30s, he was doing songs like that, this hokum-style music. On the original version, there’s a lady who sings harmony thing with him, and the guitar player is Big Bill Broonzy, and this other cat, Tampa Red — brilliant stuff. Lead guitar in a way that we understand lead guitar today, and not just fingerstyle blues from back then.

Reverend Thomas A. Dorsey became the father of modern gospel music. He wrote “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” one of the best gospel songs of all time. I spent $150 bucks for this thing 2 years ago. Back in the early ’80s, this movie came out called Say Amen, Somebody (1982), a story of the origin of gospel music out of Chicago. You’ll pay for it, but it’s worth it. You’re going to love it.

Mettker: Cool. I’m adding it to my list!

Kaukonen: Every now and then I’ll go through stuff and get rid of things, but every time I do that, I’ve wound up regretting it. But this is something you need in your collection, even if you listen to one cut once every 5 years. It’s there.

Tags: 78 rpm, Ain't in No Hurry, Al Schmitt, appointment listening, Barry Mitterhoff, Blue Country Heart, CD, Denon, Drop D tuning, Embryonic Journey, fingerpicking, Fur Peace Ranch, Garrard, Hot Tuna, Jack Casady, JBL, Jefferson Airplane, Jorma Kaukonen, Justin Guip, Larry Campbell, Levon Helm, LP, Marantz, Martin J-50, Martin M-30, Michaelson & Austin, Neve, Oppo, Polk Audio, Pultech, SACD, Sony, Surrealistic Pillow, Tannoy, Teresa Williams, Thomas A. Dorsey, Thorens

Great phone interview, appt. Listening…gotta love it!