BY MIKE METTLER — FEBRUARY 10, 2016

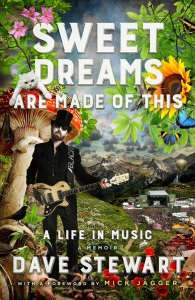

He’s a man who’s been everywhere and done it with everyone, and lived to tell the tales. He’s Dave Stewart, the production wizard best known for his indelible partnership with Annie Lennox in the uber-popular ’80s electronic duo Eurythmics. His new memoir, Sweet Dreams Are Made of This – A Life in Music (New American Library), was released on February 9, and it chronicles his wonderful life, and especially the fine sonic fruit born of collaborations with artists including Tom Petty, Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan, George Harrison, Joss Stone, and Stevie Nicks — the list could go on and on. One of the keys to Stewart’s success behind the board is how he’s able to tap into, as he puts it early in the book, “experience and experiment,” two important touchstones for him as a creative person.

He’s a man who’s been everywhere and done it with everyone, and lived to tell the tales. He’s Dave Stewart, the production wizard best known for his indelible partnership with Annie Lennox in the uber-popular ’80s electronic duo Eurythmics. His new memoir, Sweet Dreams Are Made of This – A Life in Music (New American Library), was released on February 9, and it chronicles his wonderful life, and especially the fine sonic fruit born of collaborations with artists including Tom Petty, Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan, George Harrison, Joss Stone, and Stevie Nicks — the list could go on and on. One of the keys to Stewart’s success behind the board is how he’s able to tap into, as he puts it early in the book, “experience and experiment,” two important touchstones for him as a creative person.

“I suppose it’s not being afraid to dive into the most wild and interesting situations, just to see what’s going to happen,” Stewart admits. “And vice-versa — bringing people into those kind of situations, and seeing what’s going to happen. Those are probably the two things that have happened most often in my life, yeah.”

Stewart, 63, and I got on the horn to discuss how to capture great vocal performances, his benchmark albums for great sound, and the story behind the still chilling sonics of “Love Is a Stranger.” Who am I to disagree…

Mike Mettler: You say early on in the book is that the thing that always kept you going no matter what was happening was that you always believed in the music. You kept true to that.

Dave Stewart: Yeah, I don’t know what it is — probably madness. (both laugh) But there is something in that, right — you have to believe that you won’t get ill, and then you won’t get ill, you know? I once made a t-shirt that said, “I Foresee No Problems.” If you march in thinking you’re not going to quit and that you’re going to survive, it’s probably a good thing to pass along to people. It does seem to work.

Mettler: And as Mick Jagger says in his intro to the book, you’re an “amazing enthusiast” when it comes to whatever you’re doing. That maxim seems to carry over into your productions.

Stewart: Yeah. There was one time I awoke from an operation, and I think this happens to people who’ve had a near-death experience — you wake up completely revitalized, like you’ve been plugged into an electric socket and everything is wildly interesting and exciting every day, because it’s only about perception, right? People can look at a gray day out the window and perceive it as, “Oh, it’s going to be a really boring bad day.” Somebody else might look at it and go, “Oh look, it’s a gray day. I’m going to go and write a song about it.” Or they’ll go take a photograph, do you know what I mean?

Mettler: Oh yeah. I’m the kind of person who, if I could figure out how not to need to sleep, I’d do it, because I always feel like there’s something more I want to do or experience.

Stewart: It’s such an interruption, isn’t it? (laughs) In the end, you realize it’s impossible to soak in all of the amazing things that are happening simultaneously all around the world, and what’s happening simultaneously in the body and brain. It’s impossible to comprehend.

Mettler: People like to talk about multitasking, but I don’t know how much you can really focus on at any one given time.

Stewart: There’s a theory out there where people could actually do 12 things at a time, and then scientists came back and said, “No, you can only focus on about four things at the same time without crashing.”

Mettler: Let’s focus on one thing right now and talk about your production style. You like to make sure voices are heard and are front and center in your mixes.

Stewart: Absolutely. It seems I’m an old-fashioned producer. In the days back in the ’40s and ’50s, the conductor of the orchestra was the producer. The microphone would be set for the singer, and everything was adjusted around that – moving people backwards and forwards, moving the cello section back until the voice could be heard perfectly, but so could the instruments. And then, when the voice wasn’t singing a solo, the swells of the orchestra could also be heard. Those records still sound great today — on your radio, on your vinyl player, or whatever.

Mettler: Is there any one production that stands out as the best recording for how to highlight the vocal properly? I know you grew up listening to things like Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “Oh What a Beautiful Morning,” for example.

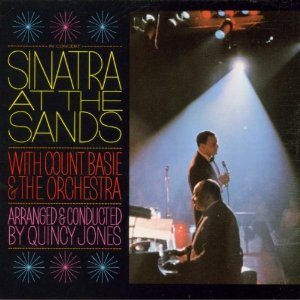

Stewart: Oh my God, well, I don’t know how they pulled it off, but it was Frank Sinatra, Sinatra at the Sands, with the Count Basie Orchestra [recorded in January and February 1966 at the Copa Room at the Sands Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas]. I mean, coping with a live recording at that time, and the sound of the band, the horn section, Sinatra’s voice — everything was just unbelievable.

Stewart: Oh my God, well, I don’t know how they pulled it off, but it was Frank Sinatra, Sinatra at the Sands, with the Count Basie Orchestra [recorded in January and February 1966 at the Copa Room at the Sands Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas]. I mean, coping with a live recording at that time, and the sound of the band, the horn section, Sinatra’s voice — everything was just unbelievable.

Mettler: Oh yeah — even Neil Peart, the drummer in Rush, has mentioned that album as being one of his favorites. [See Neil Peart’s book, Traveling Music: The Soundtrack to My Life and Times, published by ECW in 2004; pages 23-26.]

Stewart: Yeah, you listen to that on a really great system and you’re like, “Oh my God! How did he do that?” There’s this huge band, and everything sounds amazing. Of course, a lot of that has to do with the placement of the microphones and the way the players played, and the way he sings. He’s got such control. And remember — there was no “fixing” anything back then. (chuckles)

Mettler: That’s right. It was all him, and Count Basie on piano, and Quincy Jones conducting and doing the arrangements for the orchestra. There’s a lot to be said for that. And like you also say in the book, that may be a reason why someone like Adele has had such great impact. She’s a great vocalist who’s front and center in her recordings — and it’s all her. And then there’s The Beatles, of course…

Stewart: Absolutely! And, obviously, with Beatles recordings, they were often only dealing with just four tracks. And how crystal-clear [Beatles producer] George Martin got them, especially on Sgt. Pepper, where you could hear every word. Even though there was all sorts of crazy stuff going on in the recording — the use of huge orchestras, Indian instruments, those drum sounds — all sorts of things that were recorded in Studio Two in Abbey Road, a fantastic big room.

What’s funny is, when you have a big room, you can move things around like a tall curtain, and you can bang a big drum in the corner, and put the microphone 30 feet away. You can just play in that big room and players can look at each other, and you can do all sorts of experiments. The Beatles certainly used it to the maximum. That sort of creative mixture, sonically, with really great artists and a big room — it’s kind of limitless.

Mettler: And being able to get that sense of space within the recording isn’t something to be taken lightly.

Stewart: Yeah, hearing the air move all about. I guess I’m partly responsible for doing things differently — recording with a drum machine, sequencers, in a small space, singing in a vocal booth, and everything done in a tight sort of way. Well, that can be brilliant, but it’s also completely different.

When you listen to those recordings, they do different things to your mind — and your body, probably, because there’s a physical effect with the sound too, in addition to the mental effect. When you hear something that’s recorded and you can tell there’s been open mikes, and the room sound has been recorded in stereo from above, and well as with close-mikes, and the ambience that makes you feel like you’re there — it’s all very important. Think about virtual reality, where you can step inside recordings. I mean, how would you like to step inside the recording of “A Day in the Life”? However it’s interpreted visually and sonically, you want to feel like you’re inside it.

Mettler: That’s one reason why I like surround sound. And specifically to that point, I loved the way George and Giles Martin put together the fully enveloping mix for the LOVE presentation with Cirque de Soleil at The Mirage in Las Vegas.

Stewart: Yeah. I did this experiment with DTS [Headphone:X], and it’s like being in a circus tent with the knives and all sorts of things. It’s so cool. It’s all leading towards an experience that’s going to be without headphones and straightforward screens, and on into environments that you go right into.

Mettler: So I imagine higher-resolution recording must also appeal to you as a producer.

Stewart: Oh yes. It’s painful sometimes to hear things you’ve recorded come out of a cell phone as an MP3. (chuckles) You go, “Ahhh! I spent 8 hours making that sound incredible.” A lot of people are literally using their cell phones as their stereo. In the old days, people would come ’round the house or the flat just to listen to a record, but today, it’s very rare! (chuckles)

Mettler: Maybe the younger generation is getting some sense of that with the vinyl revival that’s going on now.

Mettler: Maybe the younger generation is getting some sense of that with the vinyl revival that’s going on now.

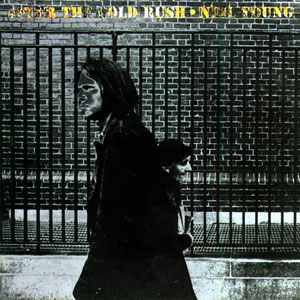

Stewart: Yeah, yeah; I know my daughter Kaya is. She’s a singer and she’s only 15, but she’s bonkers about listening to vinyl, and going to Amoeba [in Los Angeles]. And my sons Sam and Django, they’re both musicians. They understand, getting an album, and they discover things, like children do. They go, “Hey dad, have you heard of Neil Young?” And I’m like (laughs), “Um, yep!” But it’s great that they’ll suddenly dive into the whole world of Neil Young on vinyl. After the Gold Rush (1970) blows their minds.

Mettler: Oh yeah, and that’s an album from beginning to end, as soon as you drop the needle on Song 1 on Side 1, “Tell Me Why.” That’s a journey, and that’s what albums are supposed to be about — taking you on a journey.

Stewart: Yeah, absolutely. And so many albums in that period, and just before that, and after that — well, The Clash even took you on a different sort of journey, didn’t they? It was a bedraggled journey, but it was an amazing atmosphere.

Mettler: Yes. Sandinista! (1980) is basically a world trip.

Stewart: Yeah, and it puts you in a revolutionary mood! (both laugh) And other albums make you want to just flip out — albums like Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks (1968), and songs like “Into the Mystic” [from Moondance, 1970]. And you’d listen to every double-bass note by Richard Davis [on Astral Weeks].

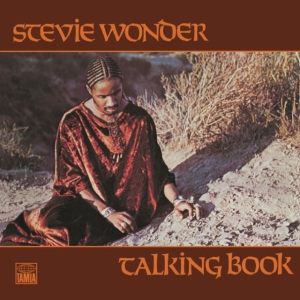

Then you go through albums like Stevie Wonder’s Talking Book (1972), which, sonically, blew my mind. And then the Sex Pistols blew my mind, with Chris Thomas’ production of those guitar sounds as well as the whole attitude [on 1977’s Never Mind The Bollocks, Here’s The Sex Pistols]. That wall of sound was like, “Whoa!!!”

Then you go through albums like Stevie Wonder’s Talking Book (1972), which, sonically, blew my mind. And then the Sex Pistols blew my mind, with Chris Thomas’ production of those guitar sounds as well as the whole attitude [on 1977’s Never Mind The Bollocks, Here’s The Sex Pistols]. That wall of sound was like, “Whoa!!!”

Mettler: John Lydon himself is a bit of an audiophile. When I talked with him last year, he said he went to the pressing plant to make sure the vinyl copies of Public Image Ltd.’s What the World Needs Now… album were up to his sonic standard.

Stewart: Absolutely, and he was obsessed with it, too. Johnny has used [dub bass master] Jah Wobble, where it was all about the low end — the big dub bass, and all that stuff. I actually used Jah Wobble on Sinéad O’Connor’s album [Faith and Courage, 2000].

Some people forget that, with a Fender Precision bass and the right valve amplifier and the right microphone at the right distance to the amplifier, you hook that with a great bass and drum, and the right drum reverb with the rim shot with the snare — if you get the right bass line, that’s the kind of thing that can make a whole festival pop and freak out. Just with that bass and drum, the whole mood of the festival changes. It becomes this sort of chilled-out dub fest.

Mettler: Rhythm is such a primal thing. You’re born to it with your mother’s heartbeat, as I like to say.

Stewart: Yeah, it’s pulsing through ya. If you fall asleep with your ear sort of inside your wrist, you wake up thinking, “What’s going on outside, an army?” [makes whizzing and whirring noises] And then you realize, “Oh, no, it’s just the blood rushing through my veins.”

Mettler: Now if you could only just record that properly…

Stewart: I have recorded that a couple of times! (laughs) I’ve recorded that with a bass and heartbeats, and slipped it into certain records. I mean, it’s limitless, the fun you can have.

In my book, I talk about when I got my first tape recorder. I went up the street and recorded somebody talking, and then I came back to my room and played it back. And that blew my mind for about 48 hours. The person wasn’t there anymore, but there was their voice on this piece of tape. I was like, “Well, that’s strange. I’m playing with time.” You know?

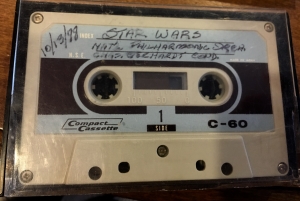

Mettler: I do. I remember back around my birthday in 1978, when my audiophile grandfather sent me a cassette of the Star Wars score by the National Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Charles Gerhardt on one side and Close Encounters of the Third Kind conducted by John Williams on the other, but he had recorded a vocal intro before both. I can still hear him saying it now, plain as day. Just to have those two things together on a recording back then was mind-blowing to me as a kid.

Mettler: I do. I remember back around my birthday in 1978, when my audiophile grandfather sent me a cassette of the Star Wars score by the National Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Charles Gerhardt on one side and Close Encounters of the Third Kind conducted by John Williams on the other, but he had recorded a vocal intro before both. I can still hear him saying it now, plain as day. Just to have those two things together on a recording back then was mind-blowing to me as a kid.

Stewart: I remember once Malcolm McLaren wanted me to combine the first song ever recorded on a phonograph, on a record, called “Algernon’s Simply Awfully Good at Algebra.” It was an old Victorian music hall song — it was rude in a way, but it was covered up in the lyrics. It was a crazy session, because “Algernon” isn’t in any sort of groovy time at all, and Malcolm wanted it to be a dance track. That was a mad session.

Mettler: When was that, what was the timeframe? What was it called?

Stewart: It was called Waltz Darling [released in 1989].

Mettler: Are you a fan of streaming music, or no?

Stewart: Well, I know it’s all just bandwidth, and streaming will get better, sound-qualitywise. I was a bit like David Bowie in that I knew it was coming. But if you look at Star Trek or any kind of futuristic movie, you can’t imagine them wandering around with CDs or bits of plastic — things just appear, right? Like, music appears, and visuals appear. That’s all definitely going to happen. You’ll have a room or a pair of glasses with earbuds — whatever it is, stuff will just come. You’ll subscribe to it and it’ll just be part of your electricity bill, or whatever.

It’s funny — music is one of the few things where it becomes less and less expensive, all the way down to free — which is annoying — but also people play it on a worse and worse players. But TV went from a tiny little box with gray dots on it all the way up to plasma screens and being attached to stereo speakers. And I’m thinking, “Why does music have to go down and backwards, and everything else gets bigger and bigger?” But it was bound to happen, because people have too much stuff! You don’t want so much stuff everywhere.

Mettler: That’s what George Carlin said back in the day, anyway.

Stewart: Yeah, yeah — and George Orwell. It comes down to being all about how you get the information.

Mettler: OK, one last thing before we go. One of my favorite tracks you’ve ever done is the Eurythmics’ “Love Is a Stranger” [the lead track on 1983’s Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This)]. I love the way the sonics of it are put together with the Omnichord toy synth and the Roland SH-01 synthesizer, and I wanted to hear from you firsthand how you did it.

Stewart: It’s a really strange track, because for a start, for a “single,” it has no form, really! (laughs)

Mettler: And there’s no chorus structure…

Stewart: No, and then it goes through nine bars, and then the next time round, the words get really strange! (chuckles) The whole thing has this happy, chirpy sort of feel and everything’s fine, and then Annie goes, “It’s vicious and it’s cruel.” It’s the ultimate sort of juxtaposition of four-on-the-floor drums and a little Japanese toy Omnichord, and then I’m playing a guitar through this — I’m playing the dee-do-dee-do-do, dee-do-dee-do-do-do, through this little tremolo, and you don’t know what it is, really.

Mettler: It’s a wobbly kind of sound, you could say.

Stewart: Yeah, and then there’s this doum-doum doum-doum. And the fills, and the crescendos, tossing all that reverb, every time she goes, “Obsessionnnn,” it goes, shwhewwwww.

We were doing it on such limited gear — a Klark Teknik spring reverb and a Roland Space Echo, which is still groovy today. And everything had to go down to seven tracks on a TEAC eight-track deck, and then be mastered onto a second-hand Revox [two-track recorder].

Again, it was all about the voice — what was she singing? How do we make it sort of bittersweet, to the utmost? How do we make the sounds go sugary-sweet, and then you realize it’s not sweet at all, you know?

Mettler: Taking your medicine in the ear, so to speak. It’s a great headphones track that still holds up to me.

Stewart: When I analyze it, I think the record company must have went, “What the hell is this?” That’s what they’d say! (laughs)

Mettler: It turned out to be a big single [reaching #23 in on the Billboard Hot 100 in November 1983], and you cut a fantastic video for it as well, with a very avant-garde feel and look to it.

Stewart: Yeah, we have Annie playing a call girl, and then next thing is she’s not a call girl, she’s a guy. And the next thing is, I’m operating her with a remote control. (chuckles) It’s all very weird.

Tags: Abbey Road, After the Gold Rush, Algernon’s Simply Awfully Good at Algebra, Amoeba Music, Annie Lennox, Astral Weeks, audiophile, Charles Gerhardt, Chris Thomas, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Count Basie, Dave Stewart, Eurythmics, Frank Sinatra, George Martin, Into the Mystic, Jah Wobble, John Lydon, John Williams, Klark Teknik spring reverb, Live at The Sands, Love Is a Stranger, LP, Malcolm McLaren, Mick Jagger, Moondance, National Philharmonic Orchestra, Neil Young, Never Mind the Bollocks, Omnichord toy synth, Public Image Ltd, Quincy Jones, Revox, Roland SH-01 synthesizer, Roland Space Echo, Sandinista, Sex Pistols, Sinead O'Connor, Stevie Wonder, streaming, Sweet Dreams Are Made of This, Talking Book, tape recorder, TEAC, The Beatles, The Clash, Van Morrison, vinyl, Waltz Darling, What the World Needs Now