BY MIKE METTLER

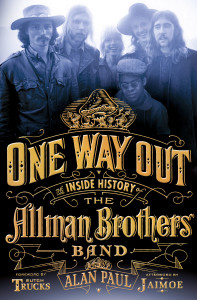

If knowledge is power, then Alan Paul is the chairman of The Allman Brothers board. His definitive inside history of The Allman Brothers Band, One Way Out (St. Martin’s Press), is one of the most thorough, in-depth, and best-researched rock biographies I’ve had the pleasure to read — and if you know me, you know I pretty much read ’em all. Though I’m a diehard Allmans fan and I’ve personally interviewed ABB members Gregg Allman, Butch Trucks, Warren Haynes, and Derek Trucks, I learned something new with just about every turn of the page. Alan’s first-hand reporting and meticulous research, presented in the oral-history format and strategically interspersed with his own insightful commentary, is so spot-on that one could almost retitle the book One Way In.

I first met Alan in early 1991 when I started writing freelance for Guitar World (he remains a senior editor there today), and whenever he’d sink his teeth into stories about the likes of Albert King, The Doors, Lynyrd Skynyrd, and ZZ Top, I knew I’d be in for a damn good read. Recently, after devouring One Way Out, I asked Alan about the highlights of The Allman Brothers Band’s recorded legacy, Duane Allman’s involvement with Layla, and what he thinks about the ABB’s infamous runs at the Beacon Theatre in New York — and whether the band will go on.

Mike Mettler: What was the most shocking and/or surprising thing you learned while researching One Way Out?

Alan Paul: Not any one thing as much as an accumulation of details helping me — and hopefully my readers — understand the dynamics of the relationships between all members of the band. Duane Allman was the one with the vision for this very different band, and he was the one everyone looked up to and he held the thing together. I knew all that, but not the full extent of his charismatic leadership and the struggles to hold it together for so many decades without him.

I also developed an even deeper understanding of the tensions that led to Dickey Betts’ ouster from the band and the extent to which being in the band with him was living in a constant state of being bullied. It all blew up in 1996 in an Idaho hotel room. I outlined the details, which involve a knife, in the book. I knew the basics, but not the specifics, until my reporting for One Way Out. It’s all complicated, because Dickey pulled the thing out of the fire after Duane’s death and was the undisputed musical leader afterwards, and they never would have had the success they did without him, but it just reached a breaking point.

I also had not really realized that [bassist] Allen Woody was basically fired from the band — and it was all because he stood up to Dickey in that hotel room.

Mettler: If you had the chance to go back in time and meet Duane Allman, what would you have asked him?

Paul: Well, I’d most like to sit in the front row and listen to him play! What I’d really be curious to know is to what extent he envisioned what the band would sound like and how he was so sure in meeting and hearing each member that they were right person for the group. His vision of this thing and his ability to find the right people amazes me.

Mettler: Same Q about Berry Oakley.

Paul: Berry and Duane had an amazing relationship. As harmonica player Thom Doucette told me, Duane would think of something he wanted done, and Berry would make it happen. [Longtime Allmans roadie] Red Dog called him The Deacon. I don’t know what my question for Berry would be. I would just like to hang out with him because he seems like an amazing guy. [Original ABB bassist Oakley died after a motorcycle accident in Macon, Georgia on November 11, 1972, three blocks from Duane’s fatal motorcycle accident on October 29, 1971.]

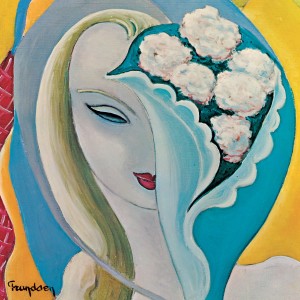

Mettler: On page 84, Eric Clapton says that he and Duane were “instant soul mates.” Would you agree? How important were The Layla Sessions to Duane as a player, and, ultimately, to The Allman Brothers Band?

Paul: I’ll have to take Eric’s word for it! By all accounts, Duane felt the same, so yes, I definitely agree. I’m not sure how important the sessions were to The Allman Brothers Band because they were on such a roll and really peaking already.

I would say that the sessions gave Duane confidence, but he never seemed to lack that. I think the sessions were certainly crucial to his overall reputation and allowed a lot more people to hear him — though a vast majority still have no idea it’s him. Most people think it’s all Eric. The fact remains that Duane wrote and played Clapton’s most famous lick, and I truly believe that Duane was who Clapton wanted to be. There’s no comparison in their playing in my mind; Duane is light years ahead.

Mettler: What’s your favorite song featuring Duane on the Layla album?

Paul: I love all of the interplay on Layla, but if I had to pick, I’d go for “Why Does Love Got to Be So Sad” or “Have You Ever Loved a Woman.”

Mettler: Do you think Dickey’s “Ramblin’ Man” changed the group’s direction and/or its leadership?

Paul: I think it reflected a change in leadership and direction more than it changed it [the band]. However, the success of the single and all that followed — stadium tours, etc. — no doubt solidified Dickey’s role as leader, not least in his own mind.

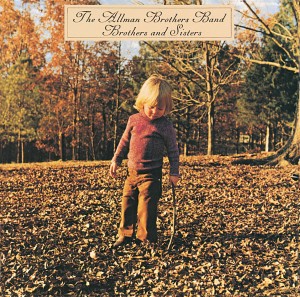

Mettler: Why is Brothers and Sisters an important album in the Allman Brothers canon?

Paul: Brothers and Sisters is a crucial album in the canon, because it definitively showed there could be life after Duane. Last year’s expanded box set is a delight, not least for a fantastic live show it includes [Live at Winterland, September 26, 1973, on Discs 3 and 4]. The way in which pianist Chuck Leavell and bassist Lamar Williams quickly and seamlessly integrated, subtly changing the band’s direction while retaining their essential nature, in the wake of the losses of Duane and Berry, is quite remarkable.

Mettler: Given the “lean years” of the mid-’70s to the late-‘80s, do you see a throughline from 1973’s Brothers and Sisters to their recording resurgence, 1990’s Seven Turns? The title track to Seven Turns is one of my personal favorite ABB songs, by the way.

Paul: Sure. Dickey Betts’ emerging leadership as a singer and songwriter for one thing, and the ability to integrate new talent and keep growing — on Brothers and Sisters with Lamar and Chuck and on Seven Turns with Warren and Woody. And I agree that “Seven Turns” is a great song.

Mettler: You’re a guitar player — what’s your personal favorite Allman Brothers songs to play?

Paul: I love playing “Blue Sky,” “One Way Out,” and “You Don’t Love Me.” I’m more of a rhythm player and singer and haven’t really tackled the more complex songs like “Jessica” and “Liz Reed.”

Mettler: What’s your favorite Allman Brothers song to just sit back and listen to?

Paul: I love listening to a lot of it, but “Dreams” and “Blue Sky” are probably my favorite kick-back songs. The former encapsulates the Gregg songs, the way they band incorporated modal jazz themes from Miles and Coltrane and Duane’s incredible depth. The latter is my favorite Dickey Betts’ major-key song and one of the finest examples of Dickey and Duane’s complementary playing.

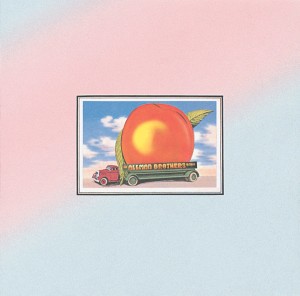

Mettler: In the Acknowledgements section of One Way Out, you mention that your brother David turned you on to Eat a Peach. What year was that, and how old were you?

Paul: That was in 1978, when I was 12 years old. I was already a music freak who carried a little transistor radio with one of those white ear pieces around listening to music all the time. I had heard The Allman Brothers on the radio plenty and certainly knew “Ramblin’ Man” and “Jessica,” which were pretty big radio hits. My first actual memory of The Allman Brothers was going with my brother to see a talent show where this dude in a fake silk shirt with a little moustache got up and sang a karaoke style version of “Ramblin’ Man.” I have no clue how he got that backing track, but I thought it was the coolest thing I had ever seen.

Mettler: What was it about Eat a Peach that hooked you on the band?

Paul: It’s hard for me to retrace my steps to being 12 and know what the attraction was, but the talk of brotherhood meant a lot to me, and the artwork on the inside gatefold fascinated me and pulled me into an alternate universe that helped the music come alive. That’s why I was so thrilled to have the same artist, W. David Powell, provide the killer artwork for One Way Out’s end pages.

Mettler: What was the first record you bought as a kid with your own money? What kind of impact did it have on you?

Paul: Man, I have no idea what was first, but I bought a lot of records at National Record Mart in Pittsburgh. I bought tons of 45s before I ever bought an LP. Some early ones I remember buying were Terry Jacks’ “Seasons in the Sun,” some Partridge Family, and Steve Miller Band’s “The Joker.” One year, my big Chanukah present was a Glen Campbell album I had begged for. I bought everything: Cheech and Chong, Allman Brothers, Lynyrd Skynyrd… all of it had a huge impact on me.

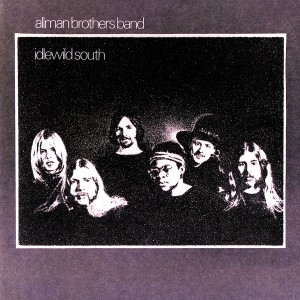

Mettler: In the Appendix, you cite Idlewild South at the top of “The Peaches” list of their best albums. Tell me a bit more why you think it’s the ABB’s greatest recorded work.

Paul: I think that “Don’t Keep Me Wondering” and “Please Call Home,” both on Idlewild, are tremendously underrated Gregg songs. It also includes “Midnight Rider,” “Revival” — which is not my favorite song, but includes heavenly guitar harmonies — and the original version of “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed.”

The other contenders would be Brothers and Sisters and Eat A Peach. The reason I chose Idlewild is B&S does not have Duane, and Eat A Peach is only a partial studio album, filled out with great live tracks. If you put a single album together of Eat a Peach studio cuts, it would include “Blue Sky,” “Melissa,” “Stand Back,” “Les Brers in A Minor,” “Little Martha,” and “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More,” and it would be a tremendous studio album.

Mettler: When was the first time you wrote about the ABB, and who was the first band member you interviewed? How did that experience go?

Paul: In 1990, I was living in Florida on the verge of giving up on being a writer and going to grad school to become a teacher. I got an assignment to write about them in Pulse. I was excited and went out and bought Dreams, their box set, and spent hours listening to it and Seven Turns. I became completely re-engrossed; the experience of writing that article was so profound to me — not just because I interviewed these guys for the first time and wrote about them, but I spent so much time listening to the music and re-immersing myself in it. I interviewed Gregg, Dickey, Warren, Woody, Phil Walden, and Tom Dowd — I went all out!

Then they came to Tampa. I hadn’t finished the article yet, and the show blew me away. It was incredible that they had reinvigorated themselves with Warren Haynes and Allen Woody. Warren made the biggest impression on me because he was standing up there with Dickey and holding his own, and they had new material, which gave them fresh life. I was still seeing The Grateful Dead, and I just started getting more and more disenchanted with their shows. I thought that these two bands were doing similar things, but The Allman Brothers were doing it a million times better.

Then I finished the article, and I went on a trip to Wyoming with my friend Art. We only had a couple of cassettes with us, and one was a 90-minute compilation I’d made from Dreams. As we drove back toward Chicago, we heard on the radio, “Tonight! The Allman Brothers at Tinley Park!” and we just looked at each other and smiled, and drove to the amphitheater. I somehow got tickets and passes from Epic Records, and it was epic! That’s why those two shows made the list.

Mettler: What did you think about Gregg Allman’s autobiography, My Cross to Bear?

Paul: I know too much about how the sausage was made to asses the meal fully, but it’s a good read that presents Gregg’s version of events.

Mettler: When and where was the first Allman Brothers show you saw? How did it affect you?

Paul: Civic Arena, Pittsburgh, 1980. I was thrilled to be there and did not realize it was a horrible era.

Mettler: How many times have you seen them to date? Do you have a particular favorite Allmans show out of all the ones you’ve seen?

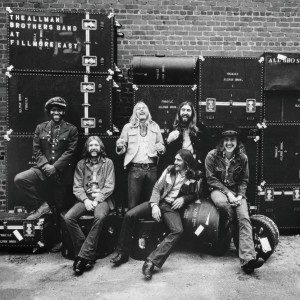

Paul: I have no idea how many shows I’ve seen. I’m not a counter. I’d like to have a nice round number to throw out there, but it’s more than 100. There have been a few favorites: the first two times I saw them with Warren Haynes blew my mind. That was 1990 — first in Tampa, then Chicago. I’ve seen so many great ones at the Beacon. In the early ’90s, Dickey and Warren were just killing it. Seeing bluesman Little Milton with them was a thrill, and their 40th anniversary run was tremendous.

Mettler: You got to see all the shows during The Allman Brothers Band’s most recent run at The Beacon Theatre in New York City, the last time they’ll do that there with both Warren Haynes and Derek Trucks as full-time member of the band. How do those shows compare with the many other Beacon shows you’ve seen? What is it about the Beacon that makes it so special to see the ABB play there?

Paul: They played 10, and I went to all of them. I don’t think it will be the last time they are there, because they had to postpone the last four and have promised to reschedule. I think they were leaning toward another fall run anyhow. We’ll see.

Every Beacon show is different, which is part of what makes them so special. There’s just something that goes on in that room, involving the band and the crowd, and the size and the way the room feels and sounds that is different. I’ve seen so many shows there that it’s hard to assess what makes them different. I thought the first few were very solid but a bit reserved, and that they got looser and looser and were really hitting a groove when the run was cancelled.

Mettler: Who do you think they’ll tap to join the band after Warren and Derek actually leave? Who would you like to see them ask to join?

Paul: I really don’t know, and it’s not clear that they will continue. I would prefer them to stop touring or go a completely different direction — like adding a pianist and a sax player or something. I don’t want to see them diminished or hiring guys to play established licks, which is contrary to the whole tradition.

Mettler: One hundred years from now, how will people view The Allman Brothers Band?

Paul: They will still sound both ancient and modern, as they have since their first album, and they will be regarded as one of the greatest rock and roll bands ever. The music does not ever sound dated or unnatural.

Tags: Alan Paul, Allen Woody, At Fillmore East, Beaon Theatre, Berry Oakley, Blue Sky, Brothers and Sisters, Butch Trucks, CD, Derek Trucks, DIckey Betts, Dreams, Duane Allman, Eat a Peach, Eric Clapton, Gregg Allman, Guitar World, Idlewild South, In Memory of Elizabeth Reed, Jaimoe, Layla, Live at the Fillmore East, LP, Midnight Rider, music, One Way Out, Ramblin' Man, The Allman Brothers Band, vinyl, W. David Powell, Warren Haynes

Thanks Mike.

My pleasure, Alan. A great book, which I hope many more folks seek out to read. Looking forward to whatever you do next.

MM

The SoundBard

[…] Mike Mettler is the former editor-in-chief of Sound & Vision, and he interviews artists and producers about their love of music and high-resolution audio on his own site, The SoundBard. An extended version of this story appears on www.soundbard.com. […]