BY MIKE METTLER — AUGUST 2, 2015

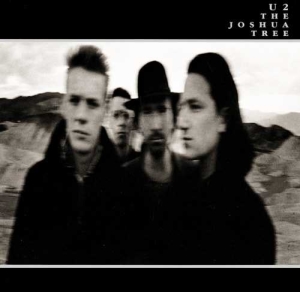

When the Irish band U2 began work on their fifth album in 1986, they had one destination in mind to capture the accompanying visual: the American West as personified by the Coachella Valley in Southern California. “We wanted to find places where nature and civilization met. The whole idea, the theme, was desert and ghost towns,” says cover designer and art director Steve Averill about the iconic late-1986 shoot that begat the indelible images used for the band’s mega-multiplatinum 1987 watershed album, The Joshua Tree (Island/UMe).

When the Irish band U2 began work on their fifth album in 1986, they had one destination in mind to capture the accompanying visual: the American West as personified by the Coachella Valley in Southern California. “We wanted to find places where nature and civilization met. The whole idea, the theme, was desert and ghost towns,” says cover designer and art director Steve Averill about the iconic late-1986 shoot that begat the indelible images used for the band’s mega-multiplatinum 1987 watershed album, The Joshua Tree (Island/UMe).

That wasn’t always the name of the record, though. “It originally had the working title The Two Americas,” Averill reveals. “The title came up during the journey, an idea Anton [Corbijn, the photographer] had to go to Joshua Tree National Park. The Biblical side of it all, and being in America, resonated with Bono and everybody else in the band, so that became the title.”

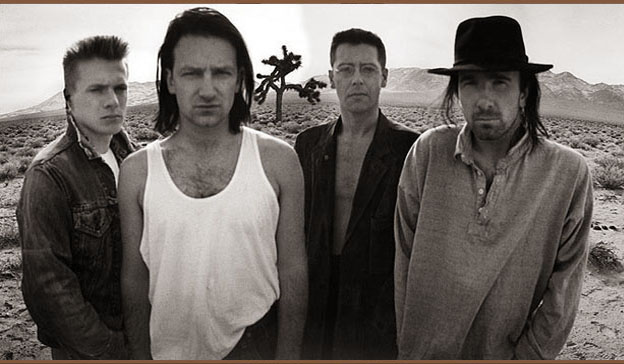

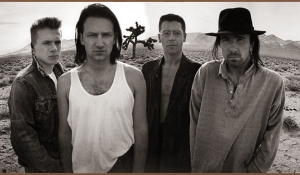

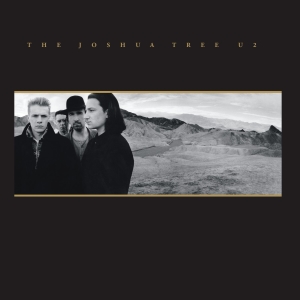

The black-and-white widescreen cover shot of the band in the foreground with such majestic valley terrain behind them was – and still is – quite a stark image to behold. “What I was trying to do with the way we shot the pictures and framed the cover was to suggest the landscape vision and cinematic approach that was taken to the recording,” explains Averill, who continues to work with the band to this day. (You can see some of his more historical handiwork in the “iNNOCENCE” portion of the current iNNOCENCE + eXPERIENCE tour book.) “My intention was to give a Sergio Leone/John Ford kind of feel to it by using a shot where the band was off to the left as opposed to being in the center.”

The cover was actually shot at Zabriskie Point, says Averill: “We were up high where the telescopes are, and we walked into the dry bed where the rainfall goes. That landscape is weird, you know? It’s kind of lunar. The American landscape is quite different from where we had been shooting in Ireland, that’s for sure. That whole area, the valley, was fairly incredible. It made you realize the size and scope of America.”

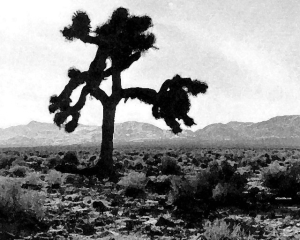

The iconic Joshua Tree itself appears to the right of the band on the back cover and also directly between them in the middle of the inside gatefold shot. Averill, Corbijn, and U2 collectively felt the cover photo of just the band and the landscape was more appropriate for where the music was going. And, sorry to be the bearer of bad news, but the fabled tree is no longer with us. “The tree has fallen down since we were there, yes,” confirms Averill. “I saw a shot of it online – it actually keeled over and died. Sad, but there you go. It was an iconic tree in itself, but it didn’t even know that it was.” And now it’s become one with the good earth of all God’s Country.

During my call to his office in Dublin, Ireland, Averill also talked about how they came across these storied locations, the quite deliberate typographical choices, and a not-so-hidden “surprise” that’s in the iconic gatefold shot. There’s no doubt that, in this case, U2 found exactly what they were looking for.

Mike Mettler: What was your initial reaction to being in the Western part of the United States?

Steve Averill: This was my first time in the States, and it was fairly incredible. It made you realize the size and scope of America. Going there really came out of discussion of the music and what the direction was. We wanted to find places where nature and civilization met. That was the theme. And initially, Anton Corbijn, the photographer, went out a week ahead of us on location scouting, and he checked all the locations he photographed.

So we set up a route plan to follow to go see which ones — which locations — were the most interesting. We were in Reno first, and then we went to Bodie in Nevada and shot for a day — a very interesting place to shoot. Death Valley Junction. It was basically freezing with snow on the ground, and within 24 hours, we were in the baking sun in the desert. It was kind of a weird experience to have that change of weather in such a short period of time, you know?

We shot in November [1986] and we knew it was going to be cold, but I didn’t think it was going to be that extreme, or get as hot. When we were shooting the actual Joshua Tree shot that’s in the center gatefold, it was actually very early in the morning, and it was cold, but it was a very still, quiet kind of cold. We deliberately made it look warmer than it actually was. People were wearing their jackets when we started out in Bodie. But when we got to the actual Joshua Tree point, it actually was very much warm.

Mettler: Were there many wardrobe changes at that point?

Averill: We had gone out with a certain, if you like, quasi-pioneer look — clothes that were based around what was worn in the 1890s — and then after that, it was what the guys wore themselves. It’s not heavily stylized in any particular way. Some of the coats of that era were researched, and then we went with the jeans and the boots, and their own style. A combination of those two things made it work.

And they’re very much ordinary guys. On that trip, we got in the coach and drove around and stayed wherever we found somewhere to stay. We didn’t stay in luxury hotels. We stayed in motels; whatever was more convenient.

Mettler: What was everyone’s reaction to being in that part of the country?

Averill: Palm Springs was much more different, much more wealthy than the other places we’d been. Reno was a totally different area and feel. Reno was one of those places we could walk around at night and nobody seemed to recognize the band, where other places as soon as they set foot out the door people recognized them. A strange experience, you know?

Mettler: Tell me about the silent footage that was shot at the Harmony Motel in 29 Palms. [This footage can be seen on the DVD that’s included in the in the Super Deluxe Edition of The Joshua Tree.]

Averill: We didn’t actually stay there. We came in around the evening, around dusk, and shot that footage. A lot of black-and-white filming was done there. Most of that 8mm footage was me. We bought an 8mm camera off the shelf, and brought a bag full of film. And whenever Anton was shooting, I would shoot the 8mm too. It was a mixture of two or three of us shooting — a lot of it very off the cuff, and some of it turned out really interesting.

Mettler: How did the band feel about that location?

Averill: Everybody was happy to be there in that location. It was a soft, casual shoot. There weren’t a load of stylists and everybody hanging around. It was very much six or eight of us working together, with a lot of humor. There always is humor when Anton is around, because he’s got a very dry sense of humor.

Visionary, Man: Steve Averill with his own crew too, The Radiators From Space. Photo by Gareth Averill.

Mettler: Are there any good humorous anecdotes you can share?

Averill: Nothing specific; there was just a lot of joshing and joking going on. Nothing stands out except one time going into a small bar near the side of the road where the coach had broken down. And of course, within 10 minutes of going into the bar, Bono is chatting up the regulars and playing pool with one of them. It came with the ease of what we were doing. Now, there are 25 or more people on a set — label people, all of that. Anton tended to work with himself, one assistant, and one stylist, and it was a much easier thing in those days, but things have changed. It’s all a little bit more complicated.

Mettler: Is the lighting in California different that what you were used to shooting with in Ireland?

Averill: Yes. We would get up and shoot early in the morning, then we’d go to a different location and shoot in the evening. We didn’t shoot in the middle of the day. We tended to get our preparation done in the meantime.

Mettler: Did you always intend for black and white instead of color?

Averill: Yes. We did shoot some color, but the intention was always black and white — that old cinematic feel, the old movies/John Ford kind of thing. If you look at the tour program that came out at the time, there are a lot of color shots in there so you could actually see the locations. Those were taken at the same time as the black-and-white photography.

Mettler: Finding the fabled Joshua Tree itself — was that the proverbial needle in the haystack?

Averill: It was purely by accident. We were driving in the coach heading toward the [Joshua Tree National] Park. Anton spotted the tree and called out to stop the coach, and we pulled over by the side of the road, because he noticed it was a tree sort of on its own — which is sort of unusual for the Joshua Tree, since they usually grow in clumps. And it was very early, like 6 o’clock in the morning, and very, very cold. We were walking across the field when the bus driver said, “You better watch out for rattlesnakes, guys.” And we all sort of froze in our tracks, and started looking around. And then he said, “Ah, it’s ok, it’s sort of cold at the moment,” and there weren’t any snakes out then.

While we were there, it was obvious we were close to an Air Force base, because one time when we were shooting, three jet planes flew very low overhead above us.

Mettler: Ahhh, “I can see those fighter planes”… So the location felt “right” for what you needed?

Averill: We always learned in a shoot that you never say this is exactly what you’re looking for, because even the Joshua Tree itself, a good shot came from happy accidents. We kind of had a broad plan, we knew what we were definitely going to do, but along the way, we’d see something and we’d stop, and we’d wander around, which we did there. The more that happened, we kept everything very, very loose and we were able to shoot wherever we felt was the right lighting, or the right place, or the right feeling in the desert.

Mettler: Do you feel The Joshua Tree shoot influenced what you did with U2 next, creatively speaking?

Mettler: Do you feel The Joshua Tree shoot influenced what you did with U2 next, creatively speaking?

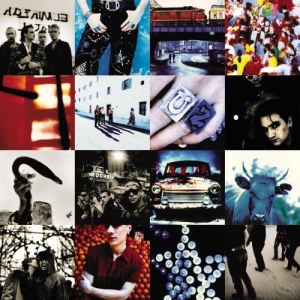

Averill: Anytime we do a cover like that, we intentionally make a point to try to move on and do something completely different. That’s why the Achtung Baby cover (1991) was so different. The Unforgettable Fire (1984) and The Joshua Tree were both cinematic in their approaches, and a few people thought they looked very serious and very grim — and, in fact, they’re not like that. They’re much more humorous, so the next time, when we came to Achtung Baby, we wanted to have fun and do a lot more different areas there.

Every band develops what we call their own language. We know very quickly there’s a certain topography and a certain style that fits in with the U2 language, and quite often when we’re working on a new U2 album cover, we take them into areas that they don’t normally go to show them what would happen if we made it a very different album cover. But usually, we get back to our own language. In the same way the band will often talk about The Beatles covers and The Stones covers, they always have a certain language that works for them. And by now, U2 have a tone and dynamic language that seems to fit for what they do. We always push the barriers of what people expect it to be. And every time you do it, you try to take it somewhere new.

The alternate, “distorted” version of the cover art, used with cassettes and some of the earlier CD packaging.

Mettler: The band name comes after the title on The Joshua Tree cover. Was there a discussion about whether the band name would come first?

Averill: Because the type is spread out, it’s a match to the widescreen effect. And I wanted “U2” to be to the righthand side because that’s where your eye tends to follow to the righthand side of a cover. In those days it wasn’t as important because these days, pricing and stickers or whatever tend to go on the right, so you have to change it around.

The interesting thing about The Joshua Tree was that because the CD was a brand-new format, we tried to experiment, and it was the only cover where the cassette, CD, and vinyl album all have different pictures on them. For a long time, when vinyl disappeared, Anton was a bit upset because what he thought was the “main” cover, the vinyl cover, wasn’t available, and all that was available was the cassette with the slightly distorted version. So we reissued that with the original cover, trying to get it as close to the vinyl cover as we could. It’s so much stronger when you get to see the full image, and especially on the gatefold when you open it up.

Go to the Mirror, Boy: Look closely at the bottom left of the shot to see what Averill is talking about… Photo courtesy of U2.com.

Anton used a panoramic camera to shoot a lot of those shots for the gatefold. It has a lens that moves, and it was usually used for pure landscape pictures. But it makes for a very interesting picture because it distorts the horizon and distorts the edges of the picture. If you look at the inside cover, you’ll notice on the very bottom left-hand corner, there’s a sort of “square” there. That’s actually a mirror we used to bring with us. We used it to make sure everybody could check out how they looked and be comfortable with it, and I didn’t realize it was in the picture at the time, but there you go. (chuckles)

Mettler: I don’t think I ever spotted that before, but now I can’t stop looking at it! So this was always intended to be a gatefold?

Averill: We’ve always liked gatefolds. Originally, the October album (1981) was to be a gatefold, but they changed that idea at the last minute, and that was something that never happened. From then on, if it was appropriate, we always went with a gatefold. And it always feels great when you pick it up and hold it. Yeah, it’s a great experience.

Mettler: You were only in the location for 3 to 5 days?

Averill: It was a full week — one weekend to the next. We spent the first few days in L.A. discussing the pictures that were taken, then we were on the roof [for the “Where the Streets Have No Name” video shoot], then we traveled up to Reno, then to Bodie down to Death Valley, then Death Valley down to Joshua Tree, then back to Los Angeles.

Mettler: What was the band reaction to the shots after everybody started looking at what you’d done?

Averill: I think they all felt really pleased. A lot of good stuff came out of that photo shoot, and everybody was in good form. Everybody enjoyed the American experience.

We fairly quickly got to the album cover. I tried one option where there was just the landscape on the cover — like a jazz ECM record, without the band. It looked good, but it wasn’t what we were really looking for. We very quickly got to the cinematic shot. Anton and I chose the shots together and tried out various things. It was quite a smooth process.

Mettler: Did the band talk about how they enjoyed being in that part of the country?

Averill: They enjoyed it. They had been around to a lot of America in their early days, so it wasn’t as new to them as it was new to me, but the company was good and the people were very friendly. It was a good time. It wasn’t quite as crazy with fans as it might be now, people who want a picture. People were inclined to let them alone a little bit more.

Mettler: In the documentary that’s on the DVD, one of Bono’s favorite phrases is, “Only in America.”

Averill: Yeah, yeah, I know, well, Italy is something as well, but, you know. (both laugh) Everybody now wants their picture taken.

Mettler: To wrap it up — in your final assessment, how successful do you feel The Joshua Tree shoot was?

Averill: Oh, very successful. The entire trip was successful on a lot of different levels. A very exciting time. My first time in the States. And what a fantastic experience to go from a city to a bleak landscape as Death Valley — but I found the desert to be calm. I have intention one day to go back there, because I really enjoyed it, being in the desert.

Mettler: Well, I think it’s safe to say The Joshua Tree is one of the most iconic albums in rock history, and the inside matches the outside in terms of what it says and stands for.

Averill: My rule of thumb has always been that the graphics of an album should inform you about the music — that it should fit what it’s about and what the music is so that you feel very much part of the same thing.

Mettler: And how do you feel about the music on the album?

Averill: I like it a lot. When they started working with Brian Eno on Unforgettable Fire, I liked the way they “expanded” things with the music. The Joshua Tree is such a great album. I’m a huge fan of all the tracks from that album.

Mettler: Me, as much as I loved all the hits and the songs that got airplay, I still always gravitate toward “Exit.” I feel it’s such a brilliant lost track, and I’m so glad its live version got extra play in the Rattle and Hum documentary (1988).

Averill: It doesn’t get the same play as some of the singles, but it was a great track too. The whole album hangs together really quite well.

Mettler: It’s timeless in its feel.

Averill: That’s a good word for it, yes. It’s timeless.

Tags: Achtung Baby, Adam Clayton, Anton Corbijn, Bono, Bullet the Blue Sky, Coachella Valley, Exit, Joshua Tree National Park, Larry Mullen Jr, October, Rattle and Hum, Steve Averill, The Edge, The Joshua Tree, The Two Americas, The Unforgettable Fire, U2, Where the Streets Have No Name, Zabriskie Point