BY MIKE METTLER I AUGUST 18, 2022

Fifty-three years ago on August 15, 1969, the Woodstock Music & Art Fair commenced at Max Yasgur’s Farm in Bethel, New York, at exactly 5:07 p.m. — i.e., the very moment rhythmic folk ’n’ soul singer/songwriter Richie Havens took to the stage. It’s quite the understatement to say that the world culture has never been quite the same ever since the very second Havens strummed the chords of “From the Prison” on his battered Guild D40 acoustic guitar, and the first sounds of Woodstock rang out into eternity.

Indeed, the deeply felt vibes of three (technically, four) days of music, communion, and collective harmony instantly catapulted that long weekend of August 15-18, 1969 directly into the history books. The zeitgeist moment that was Woodstock showed everyone how the counterculture ethos had spread and bled into the mainstream. Over half a century later, the core tenets of Woodstock are being revisited and re-evaluated by generations old and new alike in their daily lives — not to mention via the voluminous related aural/visual experiences that have been shared across many a multimedia option in the interim.

Back in 2014, I took a deep-dive look at the 45th anniversary of the event for Sound & Vision by delving into the Warner Bros. Blu-ray release dubbed Woodstock: 3 Days of Peace and Music – The Director’s Cut, 40th Anniversary Revisited. (Note: Though this BD set was indeed released to coincide with Woodstock 45, the package still had the “40th” distinction in its nomenclature.) This updated release included original location music engineer/recordist and noted producer Eddie Kramer’s surround mixes of the bonus material not in the original March 1970 movie, plus an additional, third disc called “More Extras,” including never-before-released performances from the likes of Santana, The Who, Crosby, Stills & Nash, Joan Baez, Jefferson Airplane, Melanie, Sha Na Na, and The Butterfield Blues Band. Additionally, Kramer and his team aurally chronicled career-defining performances from the likes of the aforementioned Richie Havens, Joe Cocker, Sly & The Family Stone, Janis Joplin, Ten Years After, The Who, and Jimi Hendrix (to name but a few).

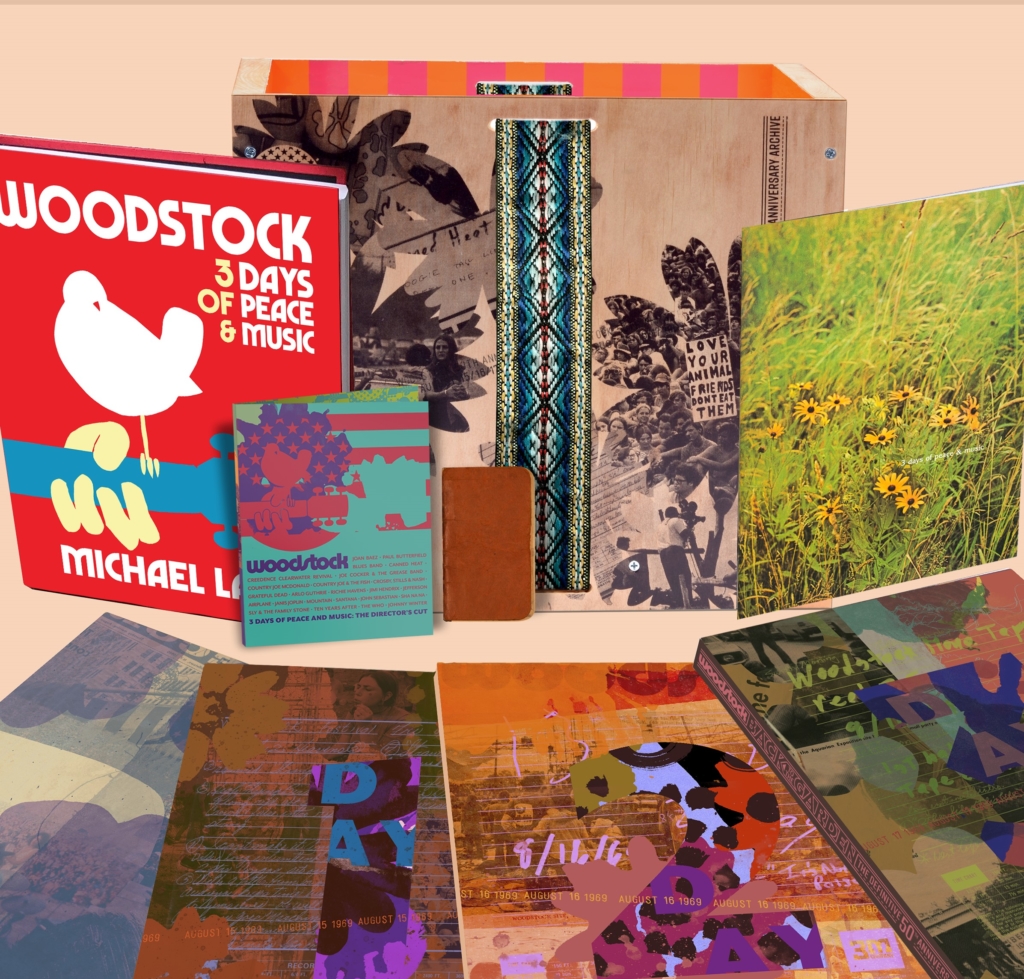

“The movie was over three hours long or whatever it was, but it was three days of music,” observed Graham Nash, who performed with Crosby, Stills & Nash (& sometimes Young) on Monday, August 18 from 3:00-4:00 a.m. in both acoustic and electric sets. “There was an incredible amount of shit that wasn’t put on there. I wanted to go through everything that wasn’t on there and go, ‘Look at this performance by John Sebastian! Put it in there!’” Though Nash himself wasn’t involved per se, he at least got his wish on the audio side of the ledger, as four songs by Sebastian duly appear on Disc 3 in Rhino’s 10CD Woodstock – Back to the Garden – 50th Anniversary Experience box set, which was released on June 28, 2019, contains 162 tracks, and is the first-ever Woodstock release to include live recordings of every performer at the festival. Upping that ante, an uber-inclusive 38CD Woodstock – Back to the Garden – The Definitive 50th Anniversary Archive collection, also from Rhino — housed in a plywood box, limited to 1,969 copies, and featuring a staggering 432 tracks and scores of memorabilia — sold out immediately at the beginning of August 2019. Additionally, more economical 3CD and 5LP versions of the 50th Anniversary Experience set were also made available in 2019, each containing 42 tracks.

Right up until the veritable last minute back in mid-August 2019, original Woodstock chief organizer Michael Lang was hopeful that an epic 50th anniversary event/celebration would occur. “Much will be updated for the 50th, and it will be a unique experience,” Lang told me personally a while back. (Sadly, Lang passed away at age 77 earlier this year, on January 8, 2022.) But for numerous reasons that were, for good or ill, somewhat salaciously played out in the press, an official Woodstock 50-branded celebratory concert was just not meant to be — and maybe that was ultimately for the best.

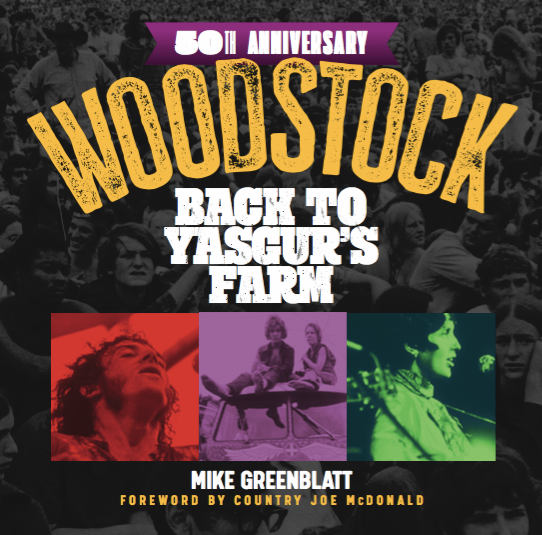

While one could fill an entire house with the amount of memorabilia that’s out there in the wake of celebrating Woodstock’s ongoing legacy, certain talismans like the aforementioned Rhino box set releases; the officially authenticated pieces of the actual performance stage that have been made available in various forms via Peace of Stage (one of which I proudly own myself, I’m happy to note!); and select books like Mike Greenblatt’s Woodstock 50th Anniversary: Back to Yasgur’s Farm, Julien Bitoun’s 50 Years: The Story of Woodstock Live, and Aidan Prewett’s Woodstock at 50: Anatomy of a Revolution, are all worth spending the requisite amount of reminiscence time with, imo.

As for me, I’m on the cusp of kicking off my own annual ritual of cuing up the Woodstock Director’s Cut and bonus performance material on Blu-ray at, oh, let’s just say, 5:07 p.m. (You can screen the full director’s cut movie via the aforementioned Blu-ray collection, or stream it via HBO Max and other streaming services.) Not only that, but I’ve also spent the past decade-plus compiling comments about Woodstock from a number the of artists who performed there themselves, along with gathering thoughts from select organizers, attendees, and influencees alike. Each year, I add more content to my master story file, and this year’s no different (hello, Robbie Robertson!). Every single quote that follows in this story has been obtained firsthand by yours truly, and I’ll continue to add to it whenever I get more information from Woodstock participants, attendees, and proponents accordingly.

It’s been a long time coming and a long time gone, so without further hippie-dippie ado, I now present to you the spirit of Woodstock as told by those who know it best, 53 years after the garden. We must be in heaven, man. . .

Mike Mettler: Here’s a simple but slightly loaded question: Did you think you’d still be talking about Woodstock today? Why do those three-plus magical days continue to resonate with you?

Michael Lang (chief festival organizer): You know, I’ve come to terms with the fact that I’m always going to be talking about it. I think it represents people’s way of being in a community and relating to each other. It was a very encouraging moment. It gave people a sense of hope around the world. In many ways, it’s stood up.

Graham Nash (harmonically gifted vocalist with Crosby, Stills & Nash — and sometimes Young — who played from 3:00-4:00 a.m. in both acoustic and electric sets on Monday, August 18, 1969): I really understand, in terms of society, how important Woodstock was. I mean, there’s a lot of that kind of vibe on our own CSNY 1974 box set [released in July 2014] — either from people who were at Woodstock, or who wished they’d been at Woodstock. I think they’re kind of reliving that hippie kind of dream, and that’s why they came to see us.

Arlo Guthrie (folk-hero vocalist/guitarist who played from 11:55 p.m.-12:25 a.m. on Friday/Saturday, August 15-16, 1969): Imagine what would happen if an insurance company announced that for the safety and well-being of their clients, fees would be waived for a year. The world would be astounded. But, that’s exactly what the promoters of the Woodstock Festival did. And I think that’s why we’re still talking about it. It set an example of human decency, even at the expense of making a fortune. We could use some more of that these days, I think.

Tom Constanten (mercurial keyboardist with The Grateful Dead, who played from 10:30 p.m.-12:05 a.m. on Saturday/Sunday, August 16-17, 1969): Our minds were already so blown. It was bigger than any of us could wrap our brains around. We knew we were onto something special, especially with all the people coming together to make music. We couldn’t quite make out what it was going to be like, but we knew that what was happening was so amazing.

Gregg Rolie (galvanizing keyboardist/vocalist with Santana, who played from 2:00-2:45 p.m. on Saturday, August 16, 1969): Nobody’s gonna let that one die, huh? (laughs heartily) Well, it was a milestone in music, it really was. Especially when the movie came out. It exploded. But nobody really knew that. “Okay, they’re making a movie; that’s great.” You’re not watching any of this happening; you’re just playing. There were many festivals back then, and this was gonna be another one. But it turned into, “If you build it, they will come,” like [1989’s] Field of Dreams — or [1977’s] Close Encounters of the Third Kind, even. It was wild. But it turned out to be that if you were there, you had a career. That was pretty much how it worked.

Melanie (nascent folk singer/guitarist who played from 10:50-11:20 p.m. on Friday, August 15, 1969): I walked onstage an unknown person, and walked off a celebrity. It was instantaneous. It was incredible. I thought it was going to be this pastoral thing — arts and crafts, with families and picnic baskets. My first concern was, “How can I possibly do this?” I’m somebody nobody’s heard of, I just have a guitar, and what am I gonna sing?” I didn’t even have a set written, or anything. I had one song that was being played by Roscoe on WNEW-FM in New York: “Beautiful People.” I think he was the only one in the whole country playing that record. So maybe a quarter of a percent of those people had heard that record. It wasn’t identifiable. I didn’t have a press photo or anything!

I was just waiting around all day to go on, and I developed this wonky, nervous cough. I guess Joan Baez heard me coughing, over from the upper-echelon tent. And her assistant, some beautiful flower child person, came over and said, “Joan has heard you coughing, and thought you might like this.” And it was a little teapot with tea in it! This was my idol, saving me!

Jocko Marcellino (charismatic drummer/vocalist of ’50s revivalists Sha Na Na – LINK: who played from 7:30-8:00 a.m. on Monday, August 18, 1969, the final set before Jimi Hendrix took the stage to close the festival an hour later, at 9:00 a.m.): Hendrix saved our slot. He got us the gig more than anybody else, after seeing us play the Steve Paul Scene [the hip midtown nightclub] in New York. He got Michael Lang to see us and book us immediately, and we got our check for 350 dollars — which bounced. (laughs) But to have our performance of “At the Hop” appear in the documentary film was just priceless, since we were a brand new act at the time. We only had a few gigs under our belt at that point.

We’ve been back there a few times since then, and it’s always great to have our feet in the Woodstock soil again at the Bethel site. But it’s backwards from what I remember of it, because they built the Bethel Woods Center down the short side of the hill. They have a plaque there on the long side of the hill, where the concert was. The piano that Joe Witkin played “At the Hop” on at Woodstock is still there in The Museum [at Bethel Woods], and the last time we were there, we took it out and played that one song on it before it blew up. (laughs)

I could have gone back after Woodstock to do other things. But I had a football coach who told me, “In life, you have windows of opportunity, but you’ve gotta see them, and go through them,” which I did. He gave me his blessing to keep playing in Sha Na Na, even though I had a football scholarship waiting for me. And we’re still rocking it every year — we do about 20-25 gigs a year, all thanks to us being at Woodstock.

Robbie Robertson (guitarist and chief songwriter of The Band, who played from 10:00 to 10:50 p.m. on Friday, August 17, 1969): The promoters, they had asked us to close the festival and play last because we were the only group actually from Woodstock! (chuckles) As Michael Lang had said at the time, the reason they called it Woodstock, and wanted to do it in Woodstock, was because of us and Bob Dylan. They said, “We think it’s appropriate that you guys close the show because of that.” And I was like, “Uh, ok! That sounds fine, I guess.” I wasn’t sure what any of it meant.

And then when we got there, they said, “Oh my God, Jimi Hendrix — we told him he could play whenever he wants, and he wants to play last.” And then they said, “We would like you to go on when it gets dark on the last night of the festival.” And we were like, “Ok!”

I had known Jimi from years before when he was Jimmy James, and he said, “Oh man, I’m sorry! I didn’t mean to make it a big deal.” And I said, “Listen — I don’t care. It’s completely fine. You can play whenever you want. We’re going to play [in the evening], then probably go back home.” (laughs) Anyway, I told him his apology wasn’t necessary.

And, as you know, Jimi played when the sun came up, when most of the people had left. But he played beautiful. And, yeah, I was glad he was happy, and I was glad everybody was happy.

[The SoundBard notes: While The Band did not appear in the original Woodstock film, their set appears on Disc 8 of Rhino’s 10CD Woodstock – Back to the Garden – 50th Anniversary Experience box-set collection.]

David Bromberg (iconic folk guitarist/vocalist who came to Woodstock to accompany folk singer/songwriter Rosalie Sorrels, who unfortunately never made it to the mainstage): Yeah, I played with Jerry Garcia [of The Grateful Dead] at Woodstock — well, it was in Jerry’s teepee, which, for some reason, I ended up in it during the rainstorm. We just played guitar together for the whole rainstorm. It was fun!

It wasn’t recorded professionally, although there is a video on YouTube of Jerry and I accompanying Rosalie Sorrels [who passed away at age 83 in 2017].

The guy who took the video thought we were playing with Mimi Fariña [noted folk singer and younger sister of Joan Baez], but it wasn’t her. It was Rosalie. I wrote to them and told them it wasn’t Mimi, but they never corrected it.

I was playing dobro. I was seated with my back to the camera, and Jerry was playing guitar, facing the camera. You can’t tell it’s me unless you know it’s me, but when I stand up, you can see. But you have to know me to see it that way.

You know, I don’t think I realized it at the time what the cultural impact of Woodstock was going to be. I tell people this, especially interviewers — I will generally tell them before an interview starts that I cannot answer overview questions, because I’m too busy looking at the trees to see the forest. And that’s also the story with Woodstock. I couldn’t see the forest.

Mettler: Let’s discuss some of the sound-related issues you had to overcome at Woodstock. Despite logistical problems with rain, wind, and a host of other physical factors, the overall soundtrack is still something to behold.

Lang: It was a big moment when Richie Havens hit the stage [at 5:07 p.m. on Friday, August 15, 1969], and the sound worked. Everybody could hear him, and he made that connection with the audience. That was a big moment of relief. We left Eddie Kramer and his crew to figure out the approach to recording. He was a pro.

The records we released [May 1970’s Woodstock: Music From the Original Soundtrack and More and July 1971’s Woodstock Two] were going to be a reflection of the soundtrack of the film, and I wanted something that had a very live feel to it that brought you back to the actual experience. The film really, really portrayed what happened that weekend in such a great way and such a visceral way that really brought the actual experience to the world. And I felt it was captured beautifully. Eddie and his crew were able to capture great live recordings without a lot of interference, feedback, and ambient noise. They just miked it well, and were able to reproduce a very true picture of the music.

Eddie Kramer (original location music engineer/recordist): The console had 12 inputs and 8 outputs, and that was it. We were using Shure 565s [microphones], which were the predecessors of the Shure 58s, for literally everything. There were no condensers. There was no double-miking. It was just a matter of trying to figure out what each band was doing as they were doing it. It was a minor miracle that anything got recorded at all. Working on the Blu-ray edition for Warner Home Video was a wonderful opportunity to set the record straight and show what it could sound like.

Mettler: Gregg, many people continue to cite Santana’s “Soul Sacrifice” as one of the hands-down best performances at Woodstock, myself included. Would you still agree with that?

Rolie: “Soul Sacrifice” is when it really came together for us, yeah. We were kind of struggling through tuning problems — you know, everybody had problems. But that’s when it was coming together. We were supposed to play hours later [on Saturday, August 16], but they threw it on us: “Well, you guys are here, and you’re going on now [at 2 p.m.].” Well, whoa, okay! So we did. Of course, we wanted to play well. The only thing to do was to focus on the playing. Santana was the kind of band where Carlos would play with his back to the audience half the time, and we’d play to each other like a jazz band.

And we played that hard every time we played, so that wasn’t unique. When we practiced, it was the same thing. There was no kidding around. Songs evolve, and the height for a player was about the soloing. I’ve heard Santana music described as jazz, guitar, B3, and Latin percussion put together. (chuckles) No matter what you call it, when you hear it, it’s unmistakable what it is, and who it is.

Mettler: Ric, your band, Ten Years After, also turned in one of the most iconic performances seen at Woodstock, especially the way your lead guitarist and vocalist, Alvin Lee, totally commanded the stage during that epic performance of “I’m Going Home.”

Ric Lee (drummer for Ten Years After, who played from 8:15-9:15 p.m. on Sunday, August 17, 1969): At that point, we were used to playing in front of festival crowds as big as 50,000, but nothing quite like what we saw at Woodstock. As the sun went down, I think we were the first act on with the stage lights. It was still like looking out at a sea of people though. We knew what was out there because we flew in over it. Since there were no screens in those days, people had to look directly at us onstage, but you couldn’t really communicate back beyond 25, maybe 30, rows out.

Mettler: Near the very end of your book From Headstocks to Woodstock, on page 292, the basic statement you make is that we need to get back to the spirit of giving to and sharing with one another to live in harmony, just like we were at Woodstock. Obviously, you wrote that about four or five years ago, but I have to imagine that it still applies to how you feel today.

Lee: Absolutely. I think the one thing why Woodstock is still so iconic is because Woodstock did exactly what was on the agenda. It was based on love.

Mettler: Now, if only somebody could have just saved the watermelon Alvin took with him off the stage after your set was over, then that could have been the most infamous piece of fruit ever.

Lee: (chuckles) Oh, that’s fantastic! That’s great. I’ve actually got a very small honeydew melon in my kitchen, and I was doing a Zoom call with somebody the other day. They said something about Woodstock, and I said, “Yeah, that’s the watermelon over there.” They probably bought it! (both laugh)

Mettler: Tom, The Grateful Dead didn’t make the final cut of the original movie for various reasons — although there is one scene of dialog with Jerry Garcia that did make it into the movie. You still had a good time performing, regardless of all the hassles you had to face, right?

Constanten: Strange to say, I had a pretty good time of it. I could hear myself and my Hammond B3 pretty well that day, and the sightlines were good — which is important. I could see and hear the other guys, good old Jerry, over there, and then the drummers [Bill Kreutzmann and Mickey Hart]. Mickey had this cannon he would fire off in this certain spot in the set, so I knew when to duck. (pauses) I hope I didn’t spoil the surprise for anyone.

When The Grateful Dead played, there were problems with the electricity and the grounding. [The Dead’s set was ultimately cut short due to the amps overloading onstage.] The guitar players [Garcia, Bob Weir, and bassist Phil Lesh] were getting shocked with the strings. I was behind the Hammond B3 organ and that wasn’t my problem, but it certainly did dampen the atmosphere in a way. The sheer weight of our equipment at the time — it wasn’t quite The Wall of Sound yet, but it was heavy. They couldn’t fit it onstage in the usual way. The way they had it set up was on this Lazy Susan that would spin around for the next act so they could play. Well, we were so heavy that the Lazy Susan was too lazy, and couldn’t get us up. (MM laughs) Meanwhile, we were feeling the stage sort of moving, which gave us a little apprehensive edge to everything.

But “Dark Star” and “Turn on Your Love Light” were both there. I look upon the performances of those pieces then as one single continuum. “Dark Star” was a piece we didn’t so much begin and end as we entered it in progress, you know? It was free and flowing and different every time. “Love Light” was much the same, although there were certain stations of the tune where Pigpen [organist/vocalist Ron “Pigpen” McKernan] would be sure to stop and do this, that, or the other, but he got pretty free and loose also.

[The SoundBard notes: The Grateful Dead do appear in the bonus material on the 2014 Woodstock Blu-ray and on Disc 5 on Rhino’s 10CD Woodstock – Back to the Garden – 50th Anniversary Experience box-set collection.]

Melanie: It started to rain [on Friday night] and I thought, “Ahhh, people are going to go home now. It’s over!” But then I hear the announcer — I think it was Wavy Gravy — saying the Hog Farm was passing out candles, and you should light the candles and hold them high to stop the rain, or something. I wasn’t really hearing it, but I absorbed it. That’s what came out in the song I wrote after Woodstock, “Candles in the Rain.”

[The SoundBard notes: “Lay Down (Candles in the Rain)” was released as a single in March 1970, and it reached No. 6 on the Billboard Hot 100 Singles chart.]

It looked like fireflies out there, coming closer and closer. It was this powerful image. When I went onstage, I had an out-of-body experience. Yeah, I wasn’t there. I finally came back to myself, and sensed that I was safe and was gonna sing my ass off (laughs). They liked me, and it was ok, and I sang a whole set. Playing “Birthday of the Sun” — it was spontaneous. I had just written that song. No one had heard it before. It was probably the only performance that ever went out publicly. After I was done, I was flying! “What was that?” It was an incredible flow of humanity toward me, and I had never experienced anything quite like it. Before that day, I don’t think I had ever sung for more than 500 people, ever. It was just me and a guitar out there.

Mettler: Ron, I hate to ask you this, but do you have any regrets about your band, Iron Butterfly, not being able to play at Woodstock in 1969?

Ron Bushy (Iron Butterfly drummer): I do. It was a real shame. We were waiting in our hotel room for them to pick us up at the Port Authority to take us there by helicopter. We went down there for it three times, but it never happened. As we found out, the choppers were being used as medivacs for dealing with things like girls having babies, ODs, etc. Our equipment was stuck in traffic, so The Who said we could borrow their equipment, but we couldn’t get in. I think Woodstock would have shot us up like a rocket. [Sadly, Ron Bushy passed away at age 79 on August 29, 2021.]

Mettler: Mike, what was it like being a Woodstock attendee? Give me the good, the bad, and the ugly.

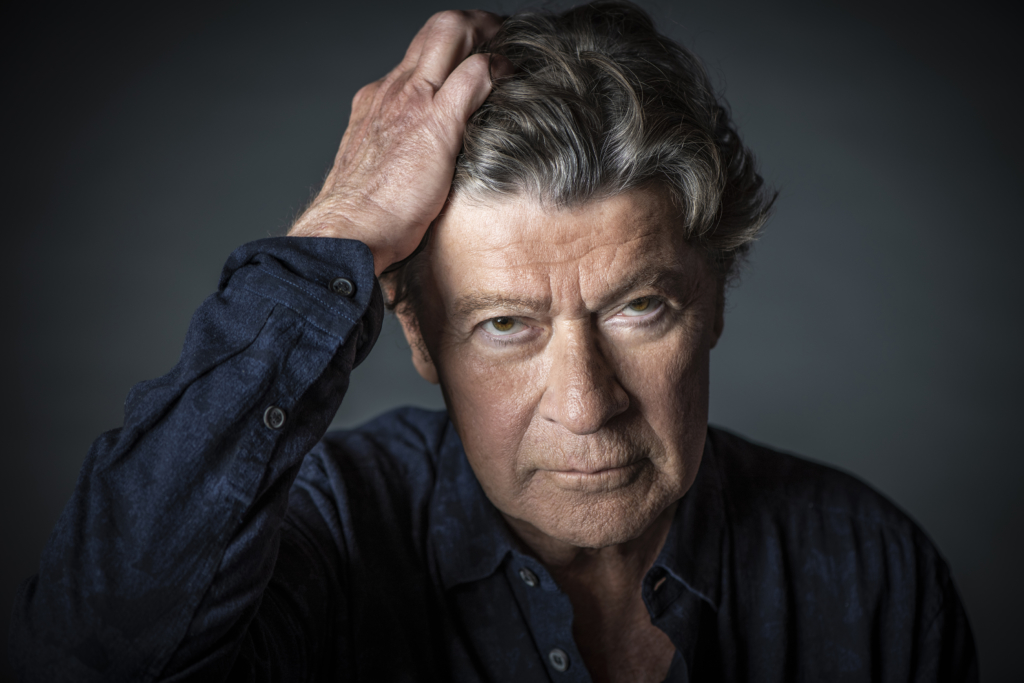

Mike Greenblatt (author of Woodstock 50th Anniversary: Back to Yasgur’s Farm): We had no idea what to expect. We weren’t even going to go, as Led Zeppelin was playing down the shore [at the Asbury Park Convention Hall in Asbury Park, New Jersey, on August 16, 1969]. But the constant ads on the radio made us realize this was a once-in-a-lifetime shot to see practically every single one of our favorite bands on the same stage in the same weekend. We bought our tickets at The Last Straw, a headshop in Bloomfield, New Jersey — $17.50 for all three days.

We went a day early, planning to camp out. Thursday, Friday, and Saturday were idyllic, but we never made it back to the car for four straight days where our tent, towels, blankets, sleeping bags, water, food, pot, and books were. I mean, did we really think we were gonna read? Sunday, the monsoon came. I was heavily tripping, and my friend Neil left to find a phone booth, so I was left alone for the three hours with no music in a heavy downpour — and I started to get paranoid. I couldn’t leave, because Neil would never find me. So, I stood there and stared at the kaleidoscopic, carnivalesque psychedelic tableau that I was trapped right in the middle of.

Mettler: Who was your favorite band or artist you saw at Woodstock, and what did you think of the soundtrack and film that both came out in 1970?

Greenblatt: My favorite performance had to be Sly & The Family Stone [who played from 3:30-4:20 a.m. on Sunday, August 17, 1969]. I had never, in my limited experience, ever heard such joyousness as we shouted, “HIGHER!” and threw up the peace sign. I also had to pee so bad that I found an empty bottle on the ground. I relieved myself, and even made a joke to my neighbors about “taking a leak on the Sly.”

I resisted the soundtrack and movie for years, although I cannot say why. I realize now that the film is groundbreaking in so many ways. Its pioneering use of split-screen for one, and how it truly captured the spirit of the weekend, what with the interviews with police at the perimeter — but not within — the festival who all said how well-behaved we were.

Mettler: A lot of songs have been written about Woodstock, probably none more revered than Joni Mitchell’s April 1970-released “Woodstock” — and she wasn’t even there! Now, I absolutely love the CSNY version that’s in the end credits of the movie, but that being said, I think Ninet Tayeb’s new, 2019 version of “Woodstock” is one of the best I’ve ever heard, and seen. [You can view it right here:

Ninet, you were born in Israel, but are now spending more and more time performing in the United States. When did you first hear the song “Woodstock,” and what did it mean to you?

Ninet Tayeb (ethereal, guttural here-and-now vocalist): I heard “Woodstock” for the first time a few years ago, but didn’t take the time to dive deep into it until fairly recently, since we were supposed to perform it at Woodstock 50 — but that event got canceled, as you know. I had read an article about why Joni Mitchell wrote this song, and it was just so fascinating to me, especially when I found out she wasn’t there. I said, “Okay, we have to do this song! We really have to make something of it!”

Joseph E-Shine, who’s the MD [music director] and producer of this song, had a great idea to make this version more upbeat, and more rock & roll. At first, I was so afraid. I wasn’t sure if we should touch this legendary song by Joni Mitchell because she’s just so untouchable, you know? But I decided I wanted to give my take on it, and make it my own. And that helped a lot, because we were very free while we were working on it — and this is what came out of it. I wanted to be there at Woodstock 50 [in 2019] so bad, so I’m feeling the lyrics from the bottom of my heart.

Mettler: I think the American phrase for it would be to call your version a “balls-out rocker.” There’s nothing held back here. By the time you get to that point at 3:21 into it and you do that extended howl and octave-jump on the word “garden,” you just take the song into another stratosphere. Nothing remains still, and I almost feel sorry for that microphone in your hand in the video, because it looks like you’re practically strangling it.

Tayeb: (chuckles heartily) Okay, that’s nice to hear! I’m so happy you noticed all that detail about the song, and that’s exactly where we wanted to take it. You can see my aggressions there, and how I poured myself into it.

Mettler: Is there one line in the song that’s the most meaningful to you? It’s hard to pick just one, but my favorite is, “I’m gonna try and get my soul free.” I feel like that line says so many things, especially today, with so many people having to fight for their personal freedom like I know you have to do yourself, every day.

Tayeb (screams): Oh my God — that’s exactly the line I was going to say! Ooh, I got the chills! That line says so much. The whole song is like a laser to me — it’s a spot of light, because it’s so powerful. Wow, I can’t believe you just said that!

And that’s what I hope you hear, because when I sing, I have to sing something I feel really, really connected to. Every line that’s written in this song — I took it from a place in my heart I didn’t even know existed before I did it. It’s almost like it came from another dimension. That’s what I feel when I sing this song.

Mettler: Okay, let’s project to the 100-year anniversary. What will people be saying about Woodstock in 2069, and beyond?

Constanten: People are going to look at the music more and the mud less. (both laugh) That’s how it works. It’s wonderful when the light shines down through the years. And it’s a wonderful thing to share that light with those who will come to it in the future.

Melanie: Oh, the mythologizing will continue. It will be bigger than life. God almighty might have been there for all I know. (laughs) It was astounding because people just did it. It was almost a silent calling, like Close Encounters of the Third Kind! It was like somewhere in dreams and people’s subconscious. They knew they had to go. They were being called.

Rolie: It is an ongoing saga of a phenomenon that has never been repeated, and I don’t think it ever will be. It’s kind of like the land rush in Oklahoma — they’re never gonna do that again either, you know? (laughs) It’s always going to be a point of history that 500,000 people got together, listened to music, and didn’t harm each other. Wow. You know? It happened.

Lang: It seems to be something rather eternal. It always represents that moment where people are shown at their best, given the possibility in the world where people relate to each other with that level of respect, in that kind of community. That’s why it’s so enduring and why it endures, really. I think it has to do with allowing the human spirit to shine through and create an environment where people can be at their best.

The interesting thing is, anyone I meet from that era — and I get recognized at film festivals, pretty much consistently — every one of them says it was life-changing for them. And I think it was life-changing in the sense of possibility, and a way to feel more open to each other. Kids pick up on that too. They look at it as a moment where they wished they could have that experience.

Most of the people who played that weekend were of the same cultural sphere as the audience. It really was the thing where the audience was the star. And it was something that the artists were striving for, and talking about, writing about, and singing about. Everybody there really felt that.