BY MIKE METTLER – NOVEMBER 22, 2016

Could it be any more fitting that Pink Floyd is the band to again raise the bar for box set presentation with their massive, 27-disc The Early Years 1965–1972 collection, out now via Pink Floyd/Columbia? The Early Years features (yes) over 49 hours of remastered and restored audio tracks and video elements on CD, DVD, and Blu-ray — with many of them presented in top-shelf 96-kHz/24-bit high-resolution form, and all very much SoundBard-approved.

In addition to heretofore unreleased mixes of early Syd Barrett tracks like “Vegetable Man” and “In the Beechwoods” as well as frame upon frame of historical video footage, the holy audio grail herein is the unreleased quad mix of “Echoes,” the groundbreaking 23-minute track from 1972’s Meddle, not to mention the quad mix of the entire Atom Heart Mother album, which was released in the 4.0 format on vinyl back in 1970, but has never really been heard properly by most listeners until now.

(And yes, we are indeed quite aware of the 5.1 mix of Meddle embedded on one of the box’s Blu-rays, but since said mix is not approved by the entire band and appears only in the form of extremely hidden and painfully difficult-to-extract audio tracks, we will withhold judgement until it is duly authorized by Pink Floyd proper.)

At any rate, yours truly sat down with founding Pink Floyd drummer Nick Mason in New York last week to discuss all things Early Years-related, and a good bit of that discussion — centering on the best of Barrett, the elements that make for a good quad mix, and what the band might do next — appears on Digital Trends. Here, exclusive to The SoundBard, Mason and I continue the thrust of that discussion by focusing on the impetus behind the first-ever live quad performance by a pop-music group, the art of miming for TV, and his favorite video-preserved moments. Breathe, breathe in the rarefied air. . .

Pink Floyd, in proper perspective. Photo by Storm Thorgerson.

Mike Mettler: You must be pleased with how this box set turned out, considering you and I first started talking about the idea of The Early Years project back in 2011.

Nick Mason: Yeah. I think it probably kicked off a long time ago when I first started trying to archive all the video footage that we either had, or didn’t have. I had some early versions of what we wanted to put on it.

Mettler: Would you agree hi-res on Blu-ray is the best way to listen to Pink Floyd music?

Mason: It is. I think so, yeah. Blu-ray is quite good. But most people aren’t really familiar with that option and how to access it properly.

Mettler: We’re working on that. If we could get the entire Pink Floyd catalog mixed in quad and/or surround sound, would that be something you’d like to have done?

Mason: Oh, I’d love to do that. And I love to hear from people like yourself who’ve heard what we’ve done so far on really good equipment. The real problem, of course, is the time needed to get everything done.

Mettler: We’ll find you the time somehow.

Mason: The trouble is, early quad was so complex in terms of being able to mix it properly. There was one studio that had a quad pan pot [on the board] for every little thing, and that was great. But it was ahead of its time, I suppose. The interesting thing is how few people were ready to put quad into their homes. It was too soon. And then by the time the iPod came along, it was all over.

Mettler: Not many artists were pleased with the results of their quad mixes back in the day. Now you at least have the chance to get surround mixes done “right” for modern listeners.

Mettler: Not many artists were pleased with the results of their quad mixes back in the day. Now you at least have the chance to get surround mixes done “right” for modern listeners.

Mason: There was a guy we worked with, Hugo Zuccarelli, who figured out how to do it with his Holophonics system.

Mettler: Right, you worked with him on [1983’s] The Final Cut.

Mason: Yes. It was brilliant when he demo’ed it. We did a lot of work on it and we did a lot of sound effects using the head [with four microphones places around a holophonic head known as “Damo”], but it never did come out that way on the record. It didn’t register.

Mettler: Maybe you can revisit that album someday again as well.

Mason: Yes, though I think there was so much of a sense that it was Roger [Waters]’s baby. If Roger had the appetite to remix that one, great. That’s another [frequent Pink Floyd surround-sound producer] James Guthrie thing. (mimes phone call) “James, what are you doing in 2025?” (both laugh)

Mettler: Let’s get back to quad. I do want to go back to the very beginning, because we’re coming up on 50 years of what I think is one of the most important things that ever happened in live popular music — namely, the Games for May event at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London on May 12, 1967, which was the very first live quad pop-music performance ever.

Mettler: Let’s get back to quad. I do want to go back to the very beginning, because we’re coming up on 50 years of what I think is one of the most important things that ever happened in live popular music — namely, the Games for May event at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London on May 12, 1967, which was the very first live quad pop-music performance ever.

Mason: The quad parts of the QEH show were absolutely groundbreaking, but in some ways, what was more groundbreaking was the idea of a band putting on an entire evening [i.e., a full two-hour show]. At the time, it was unheard of. No one band did the whole evening. You had one or more support bands, and that’s how it was.

That Hall was part of a new development, and was built particularly for classical music. I think we were probably the first band they ever had in there. It was absolutely seen as hallowed ground.

Mettler: And the idea to do live quad in the first place came out of a conversation you all had with Bernard Speight, right? [Speight was a technical engineer at Abbey Road Studios, where Pink Floyd recorded a good portion of their 1960s and early 1970s output.]

Mason: Yep, yeah. I’m not sure if it was our idea or his idea, or quite how it happened. But I would have to think he was the one who suggested it, because I can’t believe we’d have even thought about it. It was an era where we were still mainly mono. That era was Piper, and Piper [i.e., Pink Floyd’s 1967 debut album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn] was a mono album, as far as I remember.

Piper-era Floyd, circa 1967. Photo by Vic Singh.

Mettler: Piper is a great album in mono, in fact.

Mason: The problem with the early stereo albums was that they weren’t really stereo; they were just separated frequencies. There’s actually no “distribution” of the sound. And if you were working in 4-track, you had to pre-mix everything. You couldn’t go back to the original mixes. They didn’t exist. You’d already bumped over the tape.

Mettler: Right, and you had to “stack” things on the same track sometimes as well. When the initial quad idea was presented to you, do you remember your reaction? Was it like, “I never thought about that before. How can we do it”?

Mason: I thought it was brilliant. As soon as we realized we could do it, we embraced it. On some of the first tapes, we had footsteps running around, wind noise, and so on.

At the QEH, there was the thing where we actually built a table — which was, in fact, sort of the forerunner of “Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast” [from 1970’s Atom Heart Mother]. We had a whistling kettle and we had a table that we built with a sort of percussive sound, where there was the sawing of the wood, the hammering, and the dripping water.

I can’t remember if it was that show or another one where we tried to tie it in with the John Peel show on the radio where the timing would be so perfect for John to be introducing something that would be happening onstage at the show.

The big thing was that it was a two-part show, and quite a lot of it was not straightforward rock & roll. A lot of it was actually like the odd performance art. There was one guy who came on in sort of a monster costume who was a performance artist in his own right. He actually came out and sort of “pissed” on the audience through a squeezy bottle. (both laugh)

See Quad Speakers Play: Pink Floyd’s Games for May performance, May 12, 1967.

Mettler: Onstage, Rick [Wright, Pink Floyd’s keyboardist] was the one who used the Azimuth Coordinator [panning controller] to manipulate and move quad sounds around and into whatever hall you were playing. Onstage, were you able to hear any of what was going on out there, or was it impossible, given the volume you were playing at?

Mason: It was impossible. Well, partly because of volume, but in order to get the full effect, you would have to be central to the mixing station — but as players, we were always going to be more near the north speaker, really.

Mettler: You and Roger [Waters] were in charge of coming up with those additional non-musical sounds. Did you two work together on it, or separately?

Mason: No, we often worked together on the edit. We did a big edit of the DJ, Jimmy Young. By then, we must have run up against [composer and Atom Heart Mother collaborator] Ron Geesin. We learned quite a bit from the Abbey Road people, but we learned the most about how to do tape editing from Ron.

Mettler: The quad mix of Atom Heart Mother, the 1970 album you worked on with Ron, is quite something. For whatever reason, that album seems to get shunted aside, but to me, the title track is especially revelatory in 4.0.

Mason: A lot of people really like the album, but it gets shunted aside because it doesn’t quite fit with the “mainstream” tracking of where we went from Piper to Saucer [i.e., 1968’s A Saucerful of Secrets] to more or less directly to [1972’s] Meddle. It was a bit off-pieced, I think.

Mettler: On another audio note, the box set mixes of your first two singles, “Arnold Layne” and “See Emily Play,” don’t sound like of-era 1967 recordings. They’re more vibrant than what I heard of them on the original 45s I have from back then, that’s for sure.

Mettler: On another audio note, the box set mixes of your first two singles, “Arnold Layne” and “See Emily Play,” don’t sound like of-era 1967 recordings. They’re more vibrant than what I heard of them on the original 45s I have from back then, that’s for sure.

Mason: They really broke through the recording, didn’t they? Once they got onto that quality of tape, it’s extraordinary how they sound now.

There is still a bit of a problem of how to store all the material, whether it’s digital or otherwise. For a while, it was looking like DAT was going to be the medium, but it’s too “fiddly.” Hard drive seems to be the best of it at the moment, but long term, it’s still a question.

Mettler: How about the prospect of getting a Nick-centric box set by putting Fictitious Sports (1981) and Profiles (1985) together with some additional bonus material you may have in the vault?

Mason: (laughs heartily) I haven’t revisited those for a long time. I would like to see that. But there’s nothing in the vault — almost everything was used. There was a short soundtrack for something I did called Life Could Be a Dream [released in 1986] for Rothman’s — the motor racing team thing. We did a lot of music for that, but a lot of it reappeared on Profiles.

Mettler: As to the video side of the box set, is there one particular example of, “I’m really glad we were able to get X”?

Mason: I think it was the Dick Clark American Bandstand one [i.e., The Pink Floyd’s performance of “Apples and Oranges,” filmed on November 7, 1967, in Burbank, California].

Mason: I think it was the Dick Clark American Bandstand one [i.e., The Pink Floyd’s performance of “Apples and Oranges,” filmed on November 7, 1967, in Burbank, California].

Mettler: Were you actually able to eat something besides burgers [as Clark asked/suggested in the interview portion of the AB appearance]?

Mason: (laughs) Yeah. It’s a snapshot of the world we were in at that time. Some of it is very specific to us and our history and where Syd was in the time of it, but also these moments where you’d go, “Right, this is what America was like” — the era of Pan Am and 707s, and jetliners.

Mettler: Did you interact with Dick Clark at any time after that?

Mason: No. I remember doing Pat Boone as well [circa November 6, 1967] — all the American talk shows. Well, that still exists to this day, really — learning the ropes, and learning about how much “me time” you can get in.

Mettler: When you came over to the States, did you have any context for the promotional things you were doing, or was it just what you had to do?

Mason: We probably understood what it would be, because we had gotten to see American television, and we understood the sort of thing that went on in daytime television. The interesting thing is, we’d meekly go and do these terrible mime things in a studio, because we thought that was part of what you had to do.

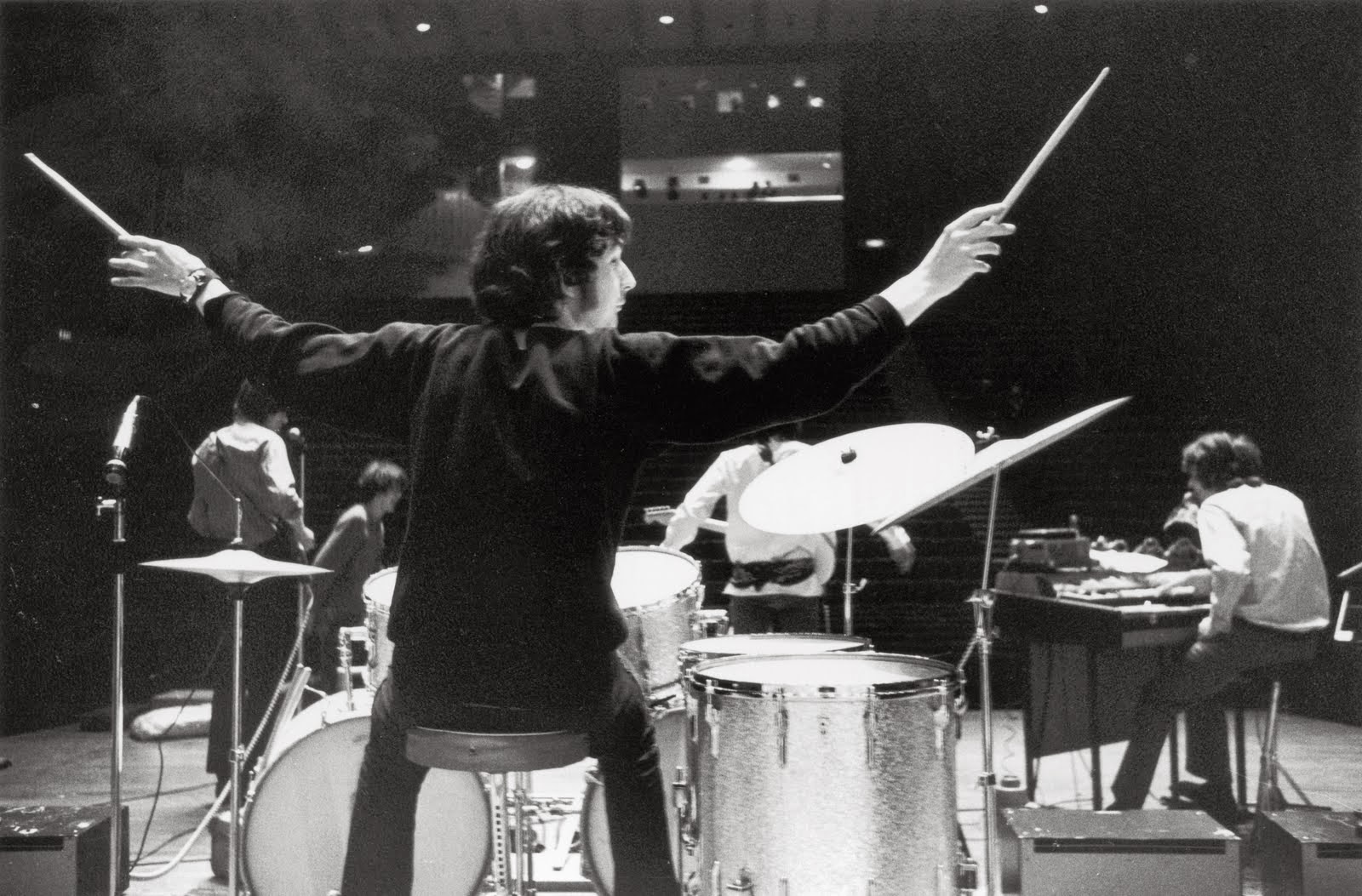

Mettler: Your role in the miming is somewhat different, because you might actually have to “hit” something on your kit and make some type of sound, where everybody else could probably get away with light strumming. Was it a skill you had to learn?

Mason: Kind of you to suggest it might be, but I can thoroughly recommend checking out some of the miming. There’s at least one where I haven’t even bothered to pick the sticks up! (both laugh) There’s this drum part where I’m sort of flapping my hands like this (mimes doing so). Magic hands! (chuckles)

Careful with those drumsticks…

Mettler: When I was re-watching Live at Pompeii on one of the Blu-rays, I was reminded how much you were a huge star of that production. We get a lot of Nick playing there.

Mason: There is a belief that one of the reasons why there is so much of me is that a can of film got lost that had David [Gilmour] or some of the others on it. This particular tracking shot was the only one they had to cover that part of the film.

Mettler: Were you surprised when you saw the cut?

Mason: Very surprised. I kept thinking, “Me? Me? (slight pause) Still me!”

Mettler: To bring things full circle, if you could give one legacy statement for Pink Floyd, what would you want people to think and understand when they hear that name in the future?

Mason: If we please some of the people some of the time, that’s all you can ask for. I don’t mind if someone says to me, “I really love the Syd Barrett era, but after that, you’ve lost me.” That’s fine. I’m happy to celebrate Syd as much as I am Dark Side or Endless River or Division Bell. And, by the way, I loved the touring for Division Bell [in 1994] and Momentary Lapse [in 1987-89]. That’s the most we ever toured. And for me, playing on those tours was really fun.

The interesting thing about this box set is, if someone had asked me 20 years ago, I would have said there’s nothing really we can release, but now we can because we can restore the film, remix the sound, and pick things out and deal with problems in a way we couldn’t 20 years ago.

Mettler: Does the Early Years box set give people a better overall historical assessment of where the band came from?

Mason: Oh, I think so. It’s pretty comprehensive. It’s not like doing a best of where you choose 15 tracks from what amounts to being our most prolific period. Along with the movie soundtracks, we produced seven or eight albums in a four- or five-year period. A best-of is an overture, not the main course.