BY MIKE METTLER – SEPTEMBER 4, 2017

Steely Dan co-founder Walter Becker passed away at age 67 on September 3, 2017, leaving behind a hi-res-oriented recorded legacy virtually unmatched by any other contemporary recording artist. As the saying goes, we may never see/hear his likes again.

Steely Dan co-founder Walter Becker passed away at age 67 on September 3, 2017, leaving behind a hi-res-oriented recorded legacy virtually unmatched by any other contemporary recording artist. As the saying goes, we may never see/hear his likes again.

To that end, we here at The SoundBard are proud to bring you my exclusive interview with Becker, which was conducted on January 25, 2005, just a few weeks after he served on a surround sound panel I hosted at CES 2005 in Las Vegas. (Incidentally, that panel also included other luminaries such as producer/engineer Elliot Scheiner and Dweezil Zappa. You know, I just may have a recording of that panel in my master files somewhere — an investigative task for another day. . .)

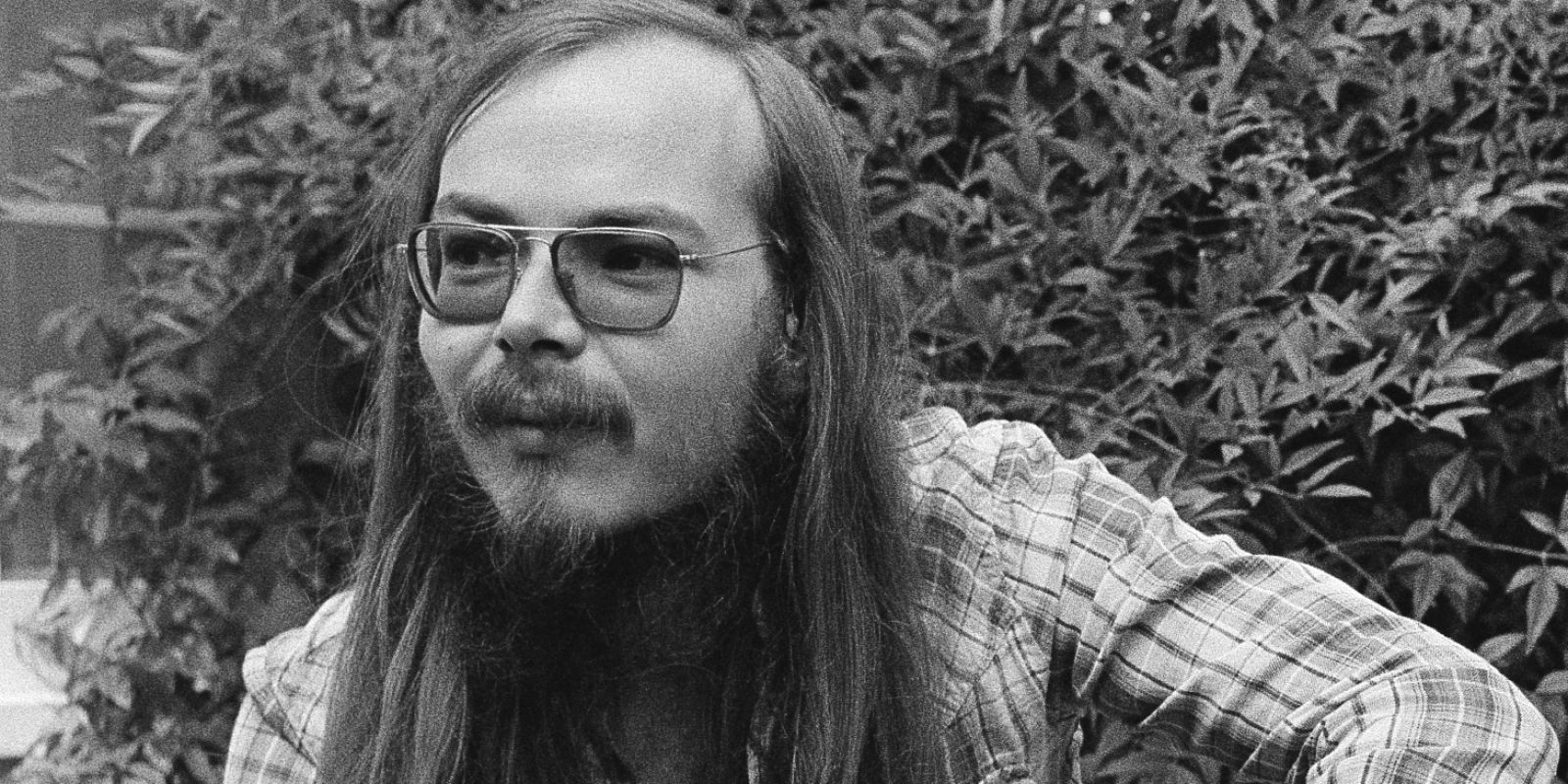

Two Against Nature: Fagen (left) and Becker. Photo by Danny Clinch.

In a statement released on September 3, 2017, Donald Fagen said of his lifelong partner in crime, “Luckily, he was smart as a whip, an excellent guitarist and a great songwriter. He was cynical about human nature, including his own, and hysterically funny. Like a lot of kids from fractured families, he had the knack of creative mimicry, reading people’s hidden psychology and transforming what he saw into bubbly, incisive art.”

When I spoke with Steely Dan touring guitarist Jon Herington in 2014, he noted that, while Becker and Fagen always knew exactly what they wanted to hear played and performed, they were quite open to creativity and interpretation from their fellow musicians. “It evolves as you listen to it,” Herington explained. “Donald and Walter have high standards about musicality. They want things in time, they want things in tune, and they want things to sound great, but they don’t expect to be ‘remaking’ the records; they don’t want that.” (You can read more of our SD-oriented interview here.)

Becker and I instantly bonded over a shared dry wit. He served; I volleyed. What follows is the bulk of our conversation from an early afternoon in January 2005, almost all of it never having appeared anywhere else — until now. Here, Becker and I discuss his surround sound philosophy, overall recording techniques, and what eventually may (or may not) be coming from the Steely Dan catalog in 5.1. RIP, o master of the 11-track whack. Yeah, you got the muscle, I got the news. . .

Mike Mettler: When did you first become aware of surround sound, as it applied to Steely Dan’s music?

Walter Becker: I think it was at the mixdown session for the original DTS version of Gaucho [which was done circa 1998], for non-movie applications.

Mettler: Did DTS come to you for that project directly?

Becker: Elliot [Scheiner, the noted producer/engineer and a longtime proponent of 5.1] arranged the whole thing.

Mettler: When you were approached about doing that mix, what was your reaction? Had you given it much thought before this? Was surround something you had to wrap your head around, literally?

Becker: No, I hadn’t given it much thought. Actually, I’m still getting used to stereo.

Mettler: Still in the Phil Spector mono mode, are you?

Becker: Well, yeah. Basically, most of the music I listen to, if I look at my rack of CDs here — there’s a rack of about 1,200 CDs on the wall here — I would say maybe 100 or 200 of them are stereo. Maybe.

Mettler: What types of things do you listen to the most?

Becker: Jazz, mainly, and Jamaican music.

Mettler: When you and Donald first started talking about surround, would it be fair to say you had to consider reinterpreting things you’d already done?

Mettler: When you and Donald first started talking about surround, would it be fair to say you had to consider reinterpreting things you’d already done?

Becker: Well, I think the thing with surround is the idea of having more channels of information and being able to bring more detail into a listening environment is in and of itself an intriguing one. But I’m not exactly sure using the existing scheme that had been developed for motion picture theaters made any particular sense for listening to music — or was a choice that was in any way optimal for music.

On the other hand, you do create discrete channels of sound, so people on the listener’s side who are interested in hearing more detail or are interested in a dimensional experience above and beyond what they can get out of a stereo recording — that’s available to them. On the artist’s side, you know, it’s a chance to refresh your relationship with old stuff that you’ve done. You revisit the master tapes, and see that they’re properly served — assuming they still exist — and then take another shot at rendering something: the music in this hybrid format.

Mettler: When you’ve talked about modern recording techniques in other interviews, you’ve said you’re able to do things now that you couldn’t even touch in the ’70s — that is, the technology wasn’t even there to help you actualize what you were thinking. You did as much as you could, but you still had limitations.

Becker: That’s true. On the one hand, limitations can be extremely conducive to creativity in a lot of ways. For example, anybody who’s ever had the experience of trying to master their music onto an LP is aware of the compromises involved — and it ain’t nuttin’ nice.

On the other hand, having 48 tracks instead of 24 tracks, or 24 tracks instead of 16 tracks, 16 tracks instead of 8 tracks, 8 tracks instead of 2, etc., has its pluses and minuses. On the plus side, you can do a whole lot of things you couldn’t do with just a few tracks, or fewer tracks.

On the minus side, because of the capability you have, the music tends to move away from the domain of creating a musical event at a particular time and a particular place with a particular set of musicians. And I think that has happened to an astonishing degree in the current situation we’re in here. People have virtually an unlimited number of tracks they can work with, and the ways they can manipulate them. They have everything they need to make astonishing music, except they don’t have any money to pay musicians.

Mettler: So limitations can help creativity. How do you get from Point A to Point B if you don’t have any “help”?

Becker: If I didn’t have any help and I had a choice between a dodgy computer with some soon-to-be-obsolete software or a rhythm section, I’ll take the real rhythm section.

Mettler: That’s a real, live feel, so good choice there.

Becker: Yeah, that’s the one thing you can’t simulate on a computer.

Mettler: Some people say Steely Dan records sound too perfect. But that wasn’t always the case, was it? You were just laying down a great-sounding bed, and maybe people misinterpret good sound as being too clean.

Mettler: Some people say Steely Dan records sound too perfect. But that wasn’t always the case, was it? You were just laying down a great-sounding bed, and maybe people misinterpret good sound as being too clean.

Becker: Working in a particular style of music was sort of jazzlike in a lot of ways. And in our experience, hearing jazz-like music being played crudely or roughly without a certain amount of precision and finesse was a very undesirable effect.

At our particular time [in the ’70s], it was the beginning of when jazz musicians were getting interested in playing over punk beats and rock & roll beats in other contexts. It wasn’t the easiest thing in the world to find guys who really could play over the changes we had in mind. Not because they were too complex — in many cases, they were too simple — it was a matter of who could play over those rhythms. It was a struggle to refine that to a point, and we took it as far as we could.

Mettler: A lot of the good rock music played in the ’60s and ’70s were played by people who knew jazz. People like Mitch Mitchell [Jimi Hendrix’s original drummer], the guys in The Doors, and Jack Bruce [of Cream] were all people who knew a bit more about jazz and theory, and they could put that stuff in there. And if people knew where it came from, great; if not, they could go discover it.

Becker: Yeah, and many of the records of the ’60s and ’70s were played by studio musicians who were either trained musicians who had backgrounds as jazz players — they weren’t primeval.

Mettler: When you and Donald were working on Two Against Nature (2000) and Everything Must Go (2003), were you thinking about surround sound at all at the outset of the recording phase?

Becker: No. Absolutely not. We’re really thinking about music when we’re making music. When it came time to do the breakouts for surround — as I recall from Two Against Nature — we did two with Elliot, and then did the rest based on that experience. That’s my recollection.

Becker: No. Absolutely not. We’re really thinking about music when we’re making music. When it came time to do the breakouts for surround — as I recall from Two Against Nature — we did two with Elliot, and then did the rest based on that experience. That’s my recollection.

In the end, we came to the conclusion that if the stuff is too spread out amongst the speakers, you end up losing some of the impact in the sense of the cohesion of the rhythm section and the record in general, so we probably ended up moving toward a giant mono sound, with a little bit of splashes of separation here and there for fun. (laughs) I don’t know if that’s the way other people do it or not.

Mettler: Some surround releases go to extremes and ping-pong things front to back, often just because they can. Do you have any personal favorites of the three Steely Dan surround releases? Any you felt were done exactly “right”?

Becker: Well, I think they were all done the way we wanted to do them at the time, and they all had a “rightness” to them that was satisfying enough at the time.

The whole point of this particular system is novelty. Not novelty in the sense of cheapness, but in terms of new effects that we haven’t heard before in music — at least not to begin with, it is. There isn’t a right way or wrong way to do it. if people are experimenting with creating some sort of striking surround effect to complement their music, they should do exactly that. Quite a bit more equipment is involved than absolutely necessary to reproduce music, and to try and impose some kind of orthodoxy on that at this point is silly.

Mettler: One of the main topics on our [January 2005] panel at CES in Vegas concerned the future of surround. Do you have a personal sense of where you think it will go?

Becker: I’m not exactly sure. I don’t have my hand on the pulse of the times. But I know many people have these sort of surround sound home theater systems. And if they became more widespread in cars, which is a fantastic place to use them, that’s probably the most satisfying use of it, when you weight the benefits and costs. In other words, the cost of having speakers all over the place, a separate subwoofer, and six channels of amplification in a car — that’s all pretty transparent. You just get in and drive, and don’t use any more space than what’s there.

Yo back atcha, Walter. . .

Mettler: Do you download music at all?

Becker: I’ve only downloaded a few things from one of the popular, legitimized sites. I like record stores — going into them, going through the racks of things, and, in some cases, talking to the person who runs the store.

On the other hand, downloading in general has exposed kids to a lot of music they would not have heard otherwise. Without weighing in on the commercial considerations involved, that is an important, good thing.

Mettler: Whenever I go to a record store, I call it “research.”

Becker: Yeah, that’s right. But at some near-future point, there may not be a Tower Records. Isn’t that unbelievable? [Tower Records maintained physical locations from 1960 to 2006.]

The most important thing to remember is there’s an idea that people weren’t going to ever need to go to the store anymore, and on one would ever go to the movies again. Most of these schemes have a Jetsonesque quality to them.

Mettler: The shared experience is dwindling. And it’s kind of hard to get digital newsprint on your fingers.

Becker: Looking at the news online is a complementary experience to reading the paper. Contemporary culture has a gadgetophile quality to it. I’m not sure how serious to take any aspect of it.

Mettler: The better mousetrap always comes along.

Becker: Like the better mouse.

Mettler: I think they’re called rats here in our town. What can we expect next from the Steely Dan canon in surround sound?

Mettler: I think they’re called rats here in our town. What can we expect next from the Steely Dan canon in surround sound?

Becker: Pretzel Logic (1974) is done, and it will be out sooner than later. The Royal Scam (1976) — we have the masters on dual 16-track [machines], and we’re just getting started there. Aja (1977) is missing some of the master tapes. At one point, we offered $600 for their return [see the liner notes to the 1999 Aja CD reissue from MCA Records for more on that], but there were no takers.

[MM’s 2017 update: I asked Elliot Scheiner about Becker’s above statements on January 31, 2005, and he confirmed to me that he had indeed competed a surround mix for Pretzel Logic, but as of this 2017 writing, it has yet to be released. The Royal Scam appears to remain in limbo to this day, and the bulk of the Aja masters are still, unfortunately, missing from the hands of their rightful owners.]

Mettler: Last question: Would it be fair to say the protagonist in “Hey Nineteen” [the first hit single from Gaucho] and “Cousin Dupree” [the main radio hit from Two Against Nature] are in some way related?

Becker: (slight pause) Ah, not. Perhaps only through some unnecessary genetic material overlap.

Mettler: We’ll have to get CSI: New York to look into that.

Becker: (laughs) Yes, let’s.